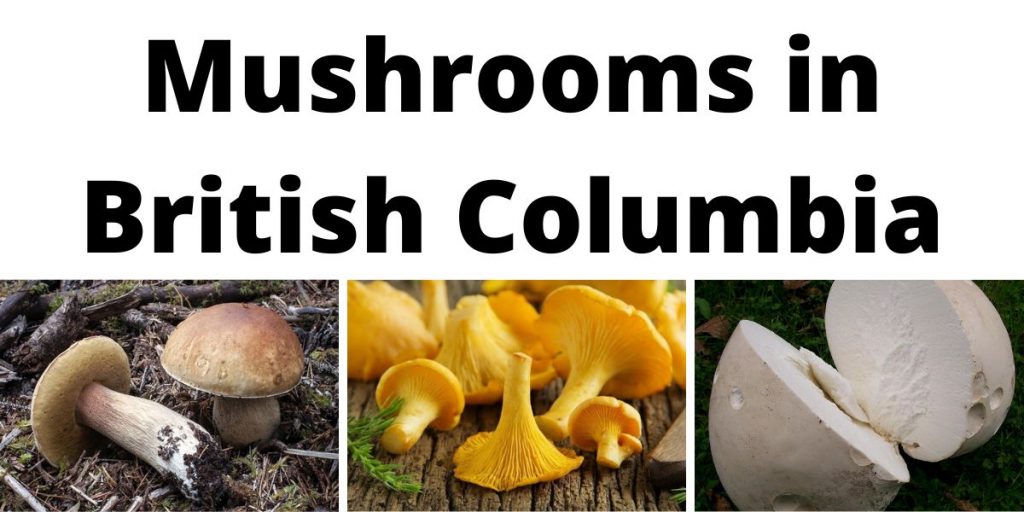

British Columbia has a mild and (mostly) well-watered climate, and is often warmer than anywhere else in Canada. Its extensive forests are a continuation of those that grow in Oregon and Washington, and are thus rich, diverse, and full of many different kinds of mushrooms. Naturally, we can’t tell you about every species out there, there are too many, but we can give you a quick introduction to what’s out there[i][ii].

Foraging for wild mushrooms isn’t a hobby for beginners. In order to be able to forage safely, it’s necessary to develop considerable expertise by collecting and identifying mushrooms without intending to eat them and, ideally, by working directly with more experienced foragers. Certainly, an article such as this one should not be taken as an instruction manual for beginners. Perhaps it can inspire you to develop your expertise.

Ensure that you have the proper tools before going mushroom hunting, take a quality knife with you and a basket/bag for your haul!

This list is not meant to be used as a replacement for a field guide, spore prints, an identification app or an in person guide.

Our Recommended Field Guides

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Edible Mushrooms

Chanterelles

Chanterelles are well-known edible mushrooms that vary from pretty good to delicious. While arguably all true chanterelles belong to the Cantharellus genus, there are some closely-related genera whose members look very similar and are mostly (not entirely) also good to eat—and are sometimes called Chanterelles. Some species have even been bounced back and forth between genera. It may be fair to say that chanterelles are the ones with ridges or veins instead of gills and that most, not all, are safe to eat.

The most famous, and most highly-prized, chanterelle is the golden, which turns out to be a complex of very closely-related species that all share the same robust trumpet-like shape and rich, yellow-orange color. British Columbia’s is the Pacific Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus). The Cascade Chanterelle (Cantharellus cascadensis) is similar, but has a whitish underside and stem and a yellow top. The Rainbow Chanterelle (Cantharellus roseocanus) is pinkish on top and yellow below. All are delicious with an oddly fruity flavor. The Yellowfoot Chanterelle (Craterellus tubaeformis) is one that has been moved between genera. It has a yellow-orange stem, but the cap has a brownish tinge. It is usually quite small. It is also more “mushroomy” in flavor than most chants, perhaps reflecting its identity as a member of a different genus. There are other Chanterelle relatives in the region, too, not all of them good to eat.

Two more species deserve mention here. Although Hedgehog Mushrooms have short spines rather than ridges, they are related to Chanterelles and taste very much like them. There are multiple hedgehog species, but British Columbia’s is probably Hydnum repandum. The Scaly Hedgehog or Hawk’s Wing (Sarcodon imbricatus) is a relative and close look-alike, but it does not always taste good.

Boletes

The Boletes are a large group of mushrooms that all share both the classic toadstool-like shape and a layer of pores rather than gills. They are considered related to each other, although they aren’t in the same genus. In fact, which genus a species is assigned to has been changing so rapidly of late that we have trouble catching up—the common names are actually more reliable! Many are edible, though there are poisonous Boletes as well. Some of the edibles are choice. Of these, The King Bolete or Porcini is perhaps the best. Unfortunately, it is now known to be a complex of similar species, and it’s not entirely clear which king or kings live in British Columbia.

Other edible Boletes in the province include the Spring King (Boletus rex-veris), the somewhat soggy-textured Zeller’s Bolete (Xerocomellus chrysenteron), and the Larch Bolete (Suillus grevillei), which has a less than excellent taste but does fruit prolifically.

Inkcaps

The Inkcaps, which turn out not to be related to each other, are notably for turning to inky, black goo upon maturity—goo is how they spread their spores. Perhaps surprisingly, many (not all) Inkcaps are safe to eat and considered quite tasty. The trick is to harvest them early and cook them quickly (within a few hours at most (before gooing can set in. Inkcap ink is edible, but if you want a mushroom, black liquid is unlikely to meet your need. British Columbia has art least three species.

Some inkcaps are frequently listed among the poisonous mushrooms, although they are not actually toxic. They do contain a chemical that makes alcohol more toxic, if the two are ingested within a few days of each other, but most people can go without alcohol for a week if they have good reason. Mica Cap (Coprinellus micaceus) and Common Inkcap (Coprinopsis atramentaria) both interfere with alcohol. Shaggy Mane (Coprinus comatus) does not.

Hericiums

Hericium is a genus of curious-looking fungi whose spores are borne on fleshy, hair-like spines that sprout, not from the underside of a cap but from all over the fruiting body. At least two live in British Columbia. Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus) is club-shaped under its spines. Bear’s Head (Hericium abietis) is branched and has much longer spines. Both are white or whitish, both fruit from dead or dying wood, and both are safe to eat with a curiously crab-like flavor. Preliminary research suggests that Lion’s Mane may have medicinal benefit, but Bear’s Head has not been the subject of such research. Its medicinal value, if any, is not known.

Puffballs

The Puffballs are a large group of fungi that all have one thing in common; their spores develop inside an entirely closed ball that either opens a single pore or ruptures at maturity. Some have a stem, others do not. Some are edible, before the spores start to mature. Others are not. Some writers assert that all true Puffballs are edible, and only false Puffballs are not, but since Puffballs as a group are defined only by their shape—most are not related to each other—any ball-shaped mushroom is a puffball, really and truly. British Columbia has at least two edible species, the Common Puffball (Lycoperdon perlatum) and the aptly-named Western Giant Puffball (Calvatia booniana).

Anyone wishing to eat a puffball must first slice it vertically and inspect the interior, which should be white and homogeneous. If the interior isn’t entirely white, then either the spores have started developing or it belongs to a poisonous Puffball species. If the interior is not homogeneous but has any kind of pattern or structure, it is not a Puffball at all and could, in fact, be deadly.

Edible Agaricus species

The genus, Agaricus once included all gilled mushrooms everywhere, but eventually mycologists figured out that was wrong and split them up. A few Agaricus species remain. These include the domestic mushroom (whose true common name actually is “mushroom,” by the way, that’s where the word comes from) and its wild relatives. Not all of these wild mushrooms are safe to eat, but a few are, and they taste very much like the domesticated version. British Columbia has at least two species, Horse Mushroom (Agaricus arvensis) and Meadow Mushroom (Agaricus campestris).

Brittlegills

The Brittlegills are the members of the genus, Russula. Most are brightly colored, many are red, and a good many are currently impossible to identify as they belong to species complexes that have not yet been well defined. Many are unpalatable or poisonous, but a few are choice edibles. The Shrimp Brittlegill[iii] is one of these. It is a species complex notable for its red or red-brown cap, its pinkish stem, and its odor of shellfish that gets stronger as the specimen ages. Some thin the mushroom tastes like shellfish, and people do like to eat it. The Yellow Swamp Russula[iv] is another choice edible. Unusually for a brittlegill, it is yellow and easy to identify. Its scientific name is Russula claroflava.

Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus sp.)

The Oyster Mushrooms are a group of related fungi that all fruit from wood and have a delicate texture and flavor. They are choice edibles, and though widely cultivated, rarely found in stores because they are difficult to ship without damage. While Oyster Mushroom species in general aren’t difficult to tell apart, British Columbia happens to be home for up to three almost identical species.

Saffron Milkcap (Lactarius sp.)

Milkcaps are the members of the genus, Lactarius, mushrooms well-known for oozing latex when cut. In some species, this latex is, indeed, milky white. In others it isn’t. Saffron Milkcaps[v] are a confusing species complex with orange “milk.” The rest of the mushroom is orange, too, but will bruise green. All members of the complex are safe to eat and delicious, but some similar orange milkcaps are not edible. The Saffron Milkcap is the most common Milkcap found in British Columbia.

Lobster Mushroom

Lobster Mushroom[vi] isn’t exactly a mushroom. It’s what happens when a mushroom (generally some species of Lactarius or Russula) is attacked by another fungus, Hypomyces lactifluorum, that grows over it as a crust. The presence of the parasite changes its host so profoundly that lobster mushroom has a consistent shape, color, texture, and flavor and is good to eat regardless of the species of the host—which can’t be easily identified.

Lobster Mushroom not only has a surface crust vaguely reminiscent of cooked lobster shell, it also has a slightly fishlike flavor. Older specimens should not be eaten, though.

Western Cauliflower Mushrooms (Sparassis radicata)

Cauliflower mushrooms[vii] do look a little bit like a head of cauliflower, though a better match might be a bowl full of noodles. In fact, the texture is so noodly it can be used as a noodle substitute in some recipes. There are multiple cauliflower mushroom species, and they all taste about this same. This is one of at least two known from Western North America.

Chicken-of-the-Woods

Chicken mushrooms, also known as sulfur shelves, are a group of species in the Laetiporus genus. All are wood-digesting shelf-fungi with pores rather than gills and distinctive coloration—most are orange and yellow, but some have white undersides or are various shades of pink. And yes, they do taste like chicken.

For many years, chicken-of-the-woods was regarded as a single species and celebrated as an easy-to-recognize edible perfect for beginners. That a few people got slightly ill from eating it was a puzzle sometimes explained as having something to do with the species of host tree. Now we know that chicken is actually a whole flock of mushroom species, each with its own range and substrate preference, and so difficult to differentiate that it’s still not entirely clear which is which. It seems not all of them are good to eat, so caution is in order.

Our Recommended Field Guides

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Poisonous Mushrooms

Given all the warnings about poisonous mushrooms, it’s easy to get the impression that most mushrooms are poisonous and will actually sicken and gill you if you so much as look at them funny. In fact, most mushrooms are safe to eat, and of the few that aren’t, even fewer are potentially deadly. Of course, avoiding the few dangerous ones is deeply important, plus there are quite a number of species that are poisonous only sometimes, under some circumstances, and that confuses matters significantly.

But not only is it important to recognize the poisonous ones in order to avoid eating them (though if a mushroom can’t be identified it shouldn’t be eaten), but these species are also fascinating in their own right. The following list does not include all toxic species in the province.

Deathcap (Amanita phalloides)

Deathcaps aren’t native to North America, but have been brought here accidentally on the roots of nursery stock. They are still most commonly found fruiting beneath trees planted in suburban or urban areas, but they can spread to wild trees, too. They are mycorrhizal, meaning the grow in partnership with tree roots and do not hurt their partners at all, though there is some suggestion that they may cause problems for native mycorrhizal species. In any case, since they do not fruit until their partners are several decades old, we are only just now learning the extent of an infestation that is by no means new.

And yes, Deathcaps are aptly-named. They do kill most people who eat them, though prompt medical attention can save some. Deathcap poisoning, like that of several other species with the same toxin, takes up to a day to show symptoms, and then symptoms seem to resolve after a few days, right before major organ failure begins—all of which complicates diagnosis.

A deathcap, like several other members of its genus, could be mistaken for a Puffball in its early “egg” stage. Amanita eggs are why all puffballs must be sliced in half prior to cooking—it’s to look for traces of the embryonic cap structure of a young Amanita. In maturity, Deathcaps are large, handsome, brownish-green mushrooms. They are most often eaten by children (or dogs) who just put things in their mouths, though they have an edible look-alike in Southeast Asia and so often tempt immigrants looking for a taste of home.

Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata)

The Deadly Galerina is also aptly-named. They contain the same toxin as the Deathcap and in similar quantities, with similar result—plus there is the added bonus that deadly galerina is a nondescript little brown mushroom and as such closely resembles several well-known edibles and most magic mushrooms. Best of all, it can grow in mixed clumps with several of its look-alikes. Always carefully identify every single mushroom headed for a human mouth. Never assume something is OK because it “looks right,” and never assume that two mushrooms are the same species just because they look the same and are growing next to each other. Check the details. Do it right. People die who don’t.

Deadly Dapperling (Lepiota subincarnata)

Dapperlings are small members of a group often referred to as parasols. Some large parasol species are well-regarded edibles, but many of the small ones are poisonous. This one, as the name implies, often kills[viii]. It is another that contains the same toxin as the Deathcap.

Wrinkled Conecap (Pholiotina rugosa or Conocybe filaris)

This pretty little species[ix] is the object of several layers of confusion. It has been known by no less than four scientific names, for example, since either of its two genus names can go with either of its two species names. It doesn’t really have two genus names, of course, one of them is right and the other isn’t, but otherwise reliable sources disagree on which is which. The two species epithets were given to what were thought to be different species, but experts disagree on whether they are really the same. Finally, some sources list this little mushroom as not recommended and possibly poisonous (or psychoactive), while others list it as deadly thanks to the same toxin that is present in the deathcap.

How can there be any doubt about its status if its toxin has been identified? Conversely, if its status isn’t known, how can its toxin be?

Best not to eat this thing anyway, though it’s hard to avoid as it closely resembles several edible and psychoactive species (and the Deadly Galerina).

Smith’s Amanita (Amanita smithiana)

Smith’s Amanita[x] does not usually kill eaters, at least not if they can get to a hospital before kidney failure progresses too far; after days or weeks on dialysis, kidney function usually restarts. The whole thing sounds deeply unpleasant, however. Most people who eat this mushroom do so because they mistake it for its edible look-alike—that the two can grow together in mixed clumps doesn’t help.

Panther Cap (Amanita pantherina) and Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria)

These two mushrooms, while quite distinct from each other, do bear a family resemblance both visually and biochemically. Both contain toxins that, while usually not deadly, are extremely unpleasant, causing severe neurological effects. As these effects include delirium, both these mushrooms are sometimes eaten by people looking to get high—and in fact, Fly Agaric has a long history of use as a psychoactive, though the active substance is not psilocybin. The trick is to carefully process the mushroom to remove the more dangerous of its several toxins. Unfortunately, not everybody knows the trick, and those who do don’t always practice it properly.

False Morel (Gyromitra esculenta)

Although called False Morel (and there is a passing resemblance), this species is seldom eaten through mistaken identity. Rather, people eat it on purpose because they don’t believe it is actually poisonous. And, actually, they have a point.

Gyromitra species contain varying amounts of a toxin that can be destroyed by cooking, although it’s important to have a well-ventilated kitchen, as the vapors released during cooking are also toxic. There is also a second toxin also present in varying amounts that is not destroyed in cooking and sometimes causes illness. The same is true (minus the need for a well-ventilated kitchen) of the celebrated morel. Lots of well-regarded edibles carry some risk and are well-regarded anyway.

But there are two other points to consider. First, this particular species may have the most toxin of any Gyromitra, so if you want to eat a false morel, this isn’t the false morel to eat. Second, there is evidence that the effects of the second toxin are cumulative, so that you could eat these mushrooms without trouble for years and then get very, very sick.

Earthball (Scleroderma bovista)

Earthballs are a group of toxic Puffballs. Though not typically deadly, their effects are very unpleasant. They differ from the edible puffballs most obviously in being more firm (like a rubber ball, rather than like a marshmallow) and in having a thicker skin. Their interior flesh also begins darkening very young, eventually becoming black.

Red Russula

Several members of the Russula genus are unpalatable or even toxic. One red and white type even bear the common names, Sickener and Emetic Russula. Unfortunately, the only thing worse than eating the Emetic Russula is trying to figure out which one it is. The taxonomy of Russulas, particularly the red or reddish ones, is the sort of cluster that mycologists only tackle when life is going too smoothly and they need more stress in their lives to spice things up.

Just don’t eat red and white Russulas.

Our Recommended Field Guides

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Magic Mushrooms

Most psychoactive mushroom species—and all those on this list—contain psilocybin, a relatively safe, but not risk-free substance that should be treated with respect. Its use and possession are illegal in Canada, and although there are large areas where such laws are not usually enforced, they still could be. Psychonauts should exercise due caution.

British Columbia has an interesting variety of psychoactive species[xi].

Gymnopilus sp.

The Gymnopilus genus is not as popular among psychonauts as some of the others, but is does have psychoactive members. Unfortunately, these species belong to a confusing complex that aren’t always possible to sort out. British Columbia has at least one member of the group.

Banded Mottlegill (Panaeolus cinctulus)

The Banded Mottlegill is a moderately psychoactive species that grows all over North America. Many of its relative are likewise psychoactive, some extremely so. But there are also non-active Panaeolus.

Psilocybe sp.

Psilocybe is the genus of some of the best-known psychoactive mushrooms in the world, including the famous Psilocybe cubensis—which doesn’t grow wild in British Columbia, the climate being way too cold. But no less than nine other members of the genus do. In rough order from least potent to most, here they are. Note that not all of them have common names.

Blue Ringers (Psilocybe stuntzii), Elf Stool (Psilocybe pelliculosa), and Blue-Haired Psilocybe (Psilocybe cyanofibrillosa) are all in the low to moderate range of potency. Psilocybe sierrae, which may be the same thing as Psilocybe fimetaria, and Psilocybe baeocystis are both comparable in potency to P. cubensis. Psilocybe silvatica, which is not well-known, the Liberty Cap (Psilocybe semilanceata), which is famous, and Wavy-Cap (Psilocybe cyanescens) all are more potent. Psilocybe fimetaria is highly variable in potency. Psychonauts take note.

Our Recommended Field Guides

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

References:

[i] (n.d.). Mushrooms Up! Beaty Biodiversity Museum

[ii] (n.d.). Wild Edible Mushrooms of British Columbia. Northern Bushcraft

[iii] (n.d.). Russula xerampelina (Schaef.) Fr.–Crab Brittlegill. First Nature

[iv] (n.d.). Russula claroflava Grove—Yellow Swamp Brittlegill.First Nature

[v] Bergo, A. (2022). Saffron Milk Cap Mushrooms: Identification, Harvesting, and Cooking. Forager/Chef

[vi] Bergo, A. (2022). Lobster Mushrooms. Forager/Chef

[vii] Bergo, A. (2022). Cauliflower Mushrooms or Sparassis: The Noodle Fungus. Forager/Chef

[viii] (n.d.). Lepiota subincarnata. Vancouver Mycological Society

[ix] Kuo, M. (2020). Pholiotina rugosa. MushroomExpert

[x] (n.d.). Amanita smithiana. Vancouver Mycological Society

[xi] (n.d.). Which Psilocybin Mushrooms Grow Wild in My Area? Shroomery