South Carolina is an interesting state, with a largely subtropical climate but much more temperate conditions in the mountains in the west. That means an interesting diversity of mushrooms, including a couple of interesting rarities. We can’t tell you about all these mushrooms, or even all the awesome ones, there are just too many[i], but we can give you a taste of what’s out there (though you definitely should not eat some of these).

The first question a lot of people ask about any mushroom is “can I eat it?” Well, fortunately, the answer is sometimes “yes.” Of course there are caveats. To begin with, don’t go out foraging on our say-so, this article is not a how-to guide. Mushroom identification is not difficult to learn, but it does have to be learned. And learning takes time and careful study.

If you do indeed go Mushroom Hunting make sure you have the proper tools, take a quality knife with you and a basket/bag for your haul!

This article is just some encouragement to help get you up that learning curve. This list is not meant to be used as a replacement for a field guide, spore prints, an identification app or an in person guide.

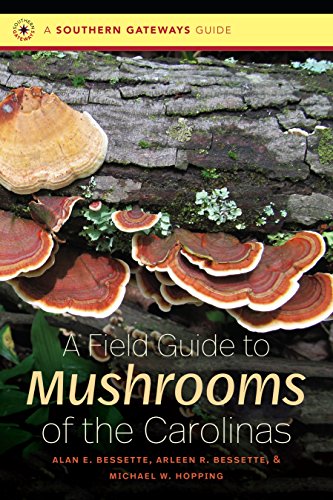

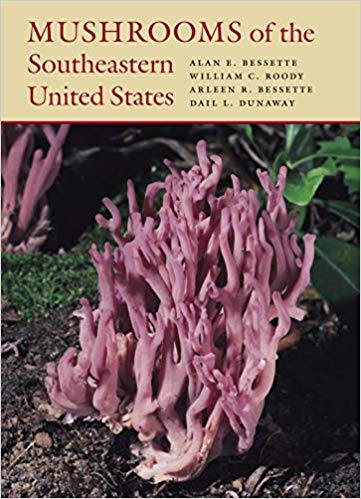

Our Recommended Field Guides for South Carolina

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Edible Wild Mushrooms

Chanterelles and Trumpets

Chanterelles and Trumpets are both more or less funnel-shaped mushrooms with ridges instead of gills. The differences between the two groups are a bit fuzzy, so some species have been moved from one to the other, as shown by the several trumpets with “chanterelle” in their common names. In any case, the members of both groups are edible and some are choice. There are a few toxic look-alikes, though, so it’s no good eating something that just looks like it’s probably a chanterelle. Identification to species is always important. It isn’t always possible, unfortunately.

The Golden Chanterelle has been recorded as resident in the state, but this is actually a species-group that hasn’t been sorted out yet, so it’s hard to say which one South Carolina has[ii]. The Smooth Chanterelle (Cantharellus lateritius) hybridizes often, producing intermediate forms[iii]. The Small Chanterelle (Cantharellus minor) looks very much like the other two except smaller, but mushrooms vary in size and there is considerable overlap[iv]. The Red Chanterelle (Cantharellus cinnabarinus) is easier—it’s red, not yellow like the others—but it has a close look-alike that may or may not be present in the Carolinas[v]. The Flame Chanterelle, or Yellowfoot, is actually a trumpet, but it’s not a single species either but another poorly-understood complex[vi]. Black trumpet is the name of multiple nearly-identical species, but the one in South Carolina is likely Craterellus fallax[vii].

Use your judgment.

Puffballs

The puffballs are a group of mostly-unrelated fungi whose fruiting bodies happen to be ball-shaped. Many are edible—some writers assert that ALL puffballs are edible, but they do that by altering the definition from “ball-shaped mushrooms” to “ball-shaped edible mushrooms.” There are definitely ball-shaped mushrooms you should not eat, whether you choose to call them puffballs or not. Plus, some non-puff mushrooms have an early “egg” stage in which they look very puffball-like, and some of these are dangerously poisonous. The rule is to identify to species—and then double-check by cutting the ball in half vertically to make sure the interior is homogeneous and white. Any hint of an internal structure means it’s not a puffball but an egg, and possibly deadly. If it’s not white, then either it’s a toxic earthball or it’s a previously edible puff that’s gotten too old to eat.

South Carolina has at least eight edible puffball species in two genera. In Lycoperdon: the Common (L. perlatum), Stump (L. pyriforme), Long-Spined (L. pulcherrimum), Pestle (L. excipuliforme), and Spiny (L. echinatum).In Calvatia: the Purple-Spored (C. cyathiformis), Eastern Giant (C. gigantea), and Brain (C. craniiformis).

Stinkhorns

Stinkhorns are an interesting group, not least because most are edible, though most Americans find them unpalatable. They are often listed as inedible, probably because I couldn’t imagine anyone eating anything that smells quite that awful. And yet some people like them, especially in the early “egg” phase (please be cautious, as several other mushrooms, including the deadly Amanita species, also have egg stages).

The other claim to fame of the group, besides the stink, is their shape. Some look, quite frankly, like long, skinny penises. Others resemble the tentacles of octopuses or strange, pink Wiffle balls. None of them have gills or pores, but instead embed their spores in patches of brown, stinky slime, called gleba. Flies come to lick up the gleba and carry away some of in their feet, which is how the spores are spread. There are multiple stinkhorn genera, but they do all seem to be related.

While most stinkhorns do seem to be edible, it’s difficult to get information on the edibility of something most mycologists don’t expect anybody to eat. Should you wish to try stinkhorns, please research the species on your menu carefully.

There are at least five stinkhorn species in South Carolina: Column Stinkhorn (Clathrus columnatus), Ravenel’s Stinkhorn (Phallus ravenelii), Devil’s Dipstick (Mutinus elegans), Anemone Stinkhorn (Aseroe rubra), and Lantern Stinkhorn (Lysurus mokusin).

Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus sp.)

The oyster mushrooms are a genus of edible, often delicious species known for their soft, delicate textures and often subtle flavors. At least some are medicinally promising, according to preliminary research. Their name reflects the slight resemblance of some species to oysters—they don’t taste oyster-like at all. Most are pale grayish or brownish, but there are brightly-colored oysters as well. Most are fan-shaped with a short stem off to the side like the handle of a fry-pan, but there are exceptions. While all oysters are edible, the group has look-alikes that are not.

South Carolina has at least two species. The oyster mushroom, the one people mean with they say “oyster mushroom” but don’t otherwise specify, is P. ostreatus[viii]. It is widely cultivated. The Summer Oyster (P. pulmonarius)[ix] is whiter and has a longer stem.

Hericiums

Lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus) eats living or dead wood and produces a large, club-shaped fruiting body covered in soft, hairlike spines. It tastes something like crab meat, and has some interesting medicinal potential, according to preliminary research. Many writers have a bad habit of treating all Hericiums as interchangeable, equally good as both food and medicine—though there’s no evidence for that, at least not yet. But the other Hericiums are edible. Besides lion’s mane, South Carolina also has Coral Tooth (H. coralloides), which branches and has shorter teeth.

Deer Mushroom (Pluteus cervinus)

Deer mushroom[x] may have gotten its name because deer like to eat it. In any case, it’s a pretty, gray-brown mushroom with a radish-like odor. Depending on how they are cooked, the radish-like flavor may or may not cook out.

They do bear a vague resemblance to the Deadly Galerina. Pay attention to detail.

Eastern Cauliflower Mushroom (Sparassis spathulata)

This is one of several species that look like, and to some extent taste like, a pile of noodles[xi]. They are easy to recognize, but quite rare.

Grisettes

The word, “grisette,” originally referred to a sort of very affordable gray cloth, and then, by extension, to the working-class French women who wore grisette clothing. Eventually, the word developed other connotations—that “a grisette” was young, flirty, possibly a sex worker…. Which of these associations were meant to apply to the mushrooms is not clear. Anyway, the Grisette Mushroom (Amanita vaginata)[xii] is a pretty little gray thing. The Tawny Grisette (Amanita fulva)[xiii] is a pretty little tawny thing. And while we’re on the subject of names, the word “vaginata” has nothing to do with human anatomy. This mushroom has a sheath-like structure around the base of its stem, and the Latin word for “sheath” is “vagina.” Apparently, an unfortunate bit of Roman slang has become weirdly persistent.

In any case, both grisettes are edible, at least if cooked properly, but since they are closely related to several deadly species and occasionally resemble them, these are not mushrooms for beginners to forage.

Our Recommended Field Guides for South Carolina

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Poisonous Mushrooms

You may have heard various rules of thumb for how to tell if a mushroom is poisonous or safe. Please ignore all of them. All such rules have exceptions, and exceptions can kill the people following the rules. There is no shortcut to learning how to identify mushroom species.

It’s worth noting that most mushrooms are not poisonous, and most of those that are produce mere unpleasantness (usually gastrointestinal upset). Of course, those few that can kill people are worth some extra attention!

It’s also worth noting that the question of safety is rarely simple. There are many mushroom species that are safe to eat sometimes, for some people, but not other times or for other people. In some cases we know what makes the difference. In other cases we do not. There are very few mushrooms that are 100% safe for everybody, but most have been eaten by at least a few people without difficulty. It’s important to educate yourself and be cautious with new species.

The following are just a few examples of poisonous mushrooms in South Carolina. There are others.

False Parasol (Chlorophyllum molybdites)

The False Parasol[xiv] is the most consistently poisonous of a group of species that are sometimes safe to eat and sometimes not. It won’t kill you (probably not, anyway), but you will not have a good time. This species is involved in more mushroom-poisoning cases than any other in the United States, perhaps because it not only resembles the (sometimes) edible parasols, but also several other popular edible species. Again, pay attention to details—especially, in this case, the detail that the spores are green.

Jack O’Lantern (Omphalotus illudens)

There are several closely-related jack o’lantern species worldwide, but this is the American one. You’ll sometimes see it listed under the name of one of the European species, but that is incorrect. Jack o’lantern Mushrooms[xv] are famous for two things: resembling Chanterelles and glowing in the dark. The glow is so faint that some experts have never managed to see it. The resemblance is also very faint, but unfortunately foragers sometimes do eat Jack o’Lanterns by accident and then get extremely sick.

Flowerpot Dapperling (Leucocoprinus birnbaumii)

The flowerpot dapperling earns its name by having hitch-hiked all over the world in the soil of potted tropical plants. It still often turns up in flowerpots, a lovely lemon-yellow, and indeed very dapper, creature. It won’t hurt your plants, as it only eats dead plant matter, nor will it hurt you, provided you do not eat the mushrooms. It’s a tropical and subtropical species, but some part s of South Carolina are warm enough for it to grow in the wild.

Earthballs

The Earthballs are sometimes regarded as False Puffballs, since everybody knows all puffballs are safe to eat and these are not, but that’s silly; a puffball is really any ball-shaped mushroom that releases puffs of spores, and these qualify. The name refers to Earthballs’ habit of only partially emerging from the ground. They differ from edible puffballs in being much more firm (imagine a rubber ball as opposed to a marshmallow) and in having dark interiors, except when extremely young. Eating an Earthball probably won’t kill you, but you will wish you had not eaten it.

South Carolina has at least two species, the Common Earthball (Scleroderma citrinum) and the Many-Rooted Earthball (Scleroderma polyrhizum). The latter is seldom found before it splits open to release its spores.

Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera)

OK, this one? If you eat it, it will kill you. Probably, anyway. Prompt medical attention by a skilled team of doctors who understand amatoxin may be able to save you. You might even avoid needing kidney and liver transplants. Do not bet on it.

There are several closely-related destroying angel species, all of them large, white or whitish, handsome gilled mushrooms. This one is the species native to the eastern US[xvi] . Although Destroying Angels are quite distinctive, they are sometimes mistaken for other mushrooms. Almost any large, white edible species, including Parasols, Ink-Caps, and some of the edible Agarics have been mixed up with the destroying angel by somebody. The early “egg” stage of the angels looks very like the eggs of some Stinkhorns and most of the small to mid-sized Puffballs. Caution is in order.

Deathcap (Amanita phalloides)

The Deathcap[xvii] looks very much like the Destroying Angels, except for having a greenish or brownish cap, and it contains the same kind of toxin and in similar amounts. So people who eat it tend to die. Historically, this mushroom has been used as a murder weapon, but most poisonings are accidents. A child, playing who tries nibbling on a mushroom or a forager who becomes overenthusiastic and under-cautious. The Deathcap is a close look-alike of a popular edible mushroom in Southeast Asia, so many poisoning victims are recent immigrants who thought they recognized a taste of home.

The Deathcap is not native to the United States but was introduced accidentally on nursery stock[xviii]. For that reason, it’s less common in wild areas and more likely to pop up in nicely-landscaped suburbs that were built in the middle of the twentieth century.

Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata)

The Deadly Galerina[xix] is another source of amatoxin, although it isn’t an Amanita—the same toxin has appeared in multiple groups of mushrooms. In any case, this one is aptly named. An alternative name, funeral bell, is also a good fit. In some older sources, you may see other Galerina species listed, but don’t be fooled, as they are really all the same. This is a rare example of taxonomists combining mushroom species instead of dividing them up.

The Deadly Galerina is an LBM (“little brown mushroom”) and, as such, is easily confused with almost any other little brown mushroom—and it’s astonishing how many mushroom species are little and brown or brownish. A number of popular culinary species and nearly all of the psychoactive mushrooms are LBMs. Worse, Deadly Galerina can sometimes grow in mixed clumps with its look-alikes, so that you might come upon a group of ten nearly-identical-looking mushrooms, carefully and correctly key out six of them, one after the other, find that all six are something safe and delicious, so you harvest all ten, cook them up, and die a week later because the other four were Deadly Galernia.

It’s not that mushroom identification is impossible or unreliable, it’s that you have to know what you’re doing, and you have to do it. No making assumptions or skipping steps.

Our Recommended Field Guides for South Carolina

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Magic Mushrooms

Magic, that is, psychoactive, mushrooms are mostly those that contain psilocybin. Use or possession of psilocybin is against US Federal law and against the law in most states, including South Carolina[xx]. Penalties can be draconian. But several psilocybin-containing mushroom species do grow wild in the state.

Please note that harvesting these mushrooms if you are not an expert forager is a really bad idea, even aside from the law. For example, say you are used to buying or growing psilocybin mushrooms and are familiar with what they look like. You see something growing wild that looks just like your favorite shrooms. Should you take a bite?

No!

Magic mushrooms are small, nondescript, brownish or grayish, and hard to differentiate from zillions of other small, nondescript, brownish or grayish mushrooms—some of which will kill you if you eat them. Only people who are familiar with the process of identifying wild mushrooms to species should consider harvesting these.

Gymnopilus sp.

There are several species of “gyms,” but the taxonomy of the group is a bit confused, so it’s hard to say which is which. These are not very popular as psychoactive mushrooms go, so it’s hard to get information on what using them is really like, but reportedly it qualitatively a little different from the high caused by most of the other psilocybin-containing mushrooms.

Panaeolus sp.

These are the Mottlegills, so called because their gills become mottled as the spores develop unevenly in patches. Not all mottlegills are psychoactive at all, while some, like Panaeolus cyanescens, are extremely potent—that’s the “Blue Meanie,” a name that unfortunately also belongs to a cultivated strain of Psilocybe cubensis. The two should not be confused, as their strengths differ. P. cinctulus, the Banded Mottlegill, is more mid-range in potency. Both grow in South Carolina.

Psilocybe sp.

This is the genus of P. cubensis, a psychoactive species made famous by, in part, the fact that it’s easy to cultivate. Parts of South Carolina are warm enough for it to grow wild, though. P. caerulescens is another subtropical species found in South Carolina, but slightly less potent. It’s also rare in the state. P. caerulipes is known as “little blue-foot” and should not be confused with “Blue Meanie.” P. tampanensis is also rare, but does turn up occasionally, and has the distinction of producing truffle-like stones as well as mushrooms.

Our Recommended Field Guides for South Carolina

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

References:

[i] (n.d.). Observations: South Carolina. iNaturalist

[ii] Kuo, M. (2015). Cantharellus “cibarius.” MushroomExpert

[iii] Kuo, M. (2015). Cantharellus lateritius. MushroomExpert

[iv] Kuo, M. (2015). Cantharellus minor. MushroomExpert

[v] Kuo, M. (2015). Cantharellus cinnabarinus. MushroomExpert

[vi] Kuo, M. (2015). Craterellus tubaeformis. MushroomExpert

[vii] Kuo, M. (2015). Craterellus cornucopiodes. MushroomExpert

[viii] Kuo, M. (2017). Pleurotus ostreatus. The MushroomExpert

[ix] Kuo, M. (2017). Plueurotus pulmonarius. TheMushroomExpert

[x] Bergo, M. (n.d.). Deer Mushrooms: Pluteus cervinus and pestatus. Forager/Chef

[xi] Bergo, M. (n.d.). Cauliflower Mushrooms: The Noodle Fungus. Forager/Chef

[xii] (n.d.). Amanita vaginata (Bull.) fr. –Grisette. First Nature

[xiii] (n.d.). Amanita fulva (Schaeff.) fr. –Tawny Grisette. First Nature

[xiv] Kuo, M. (2020). Chlorophyllym molybdites. MushroomExpert

[xv] Kuo, M. (2015). Omphalotus illudens. MushroomExpert

[xvi] Kuo, M. (2013). Amanita bisporigera. MushroomExpert

[xvii] (n.d.). Amanita phalloides (Vaill. Ex Fr.) Link—Deathcap. First Nature

[xviii] Childs, C. (2019). Death-Cap Mushrooms Are Spreading Across North America. The Atlantic

[xix] Volk, T. (2003). Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for May 2003. Tom’s Fungi

[xx] Dubley, P. (2022). Are Psychedelics Legal in South Carolina? Tripsitter