Virginia has an interesting diversity of wild mushrooms[i], perhaps because the state covers so many habitat types, from the seashore to the mountains. Some are edible mushrooms and some are very much not. Some occupy one or another kind of strange middle-ground, from the morels that are safe to eat sometimes to the “magic” mushrooms that intoxicate in ways many people like. No quick internet article can ever do more than scratch the surface of a whole state’s mushroom diversity, but an introduction to some of the better-known species should help.

Always get help from an expert when foraging mushrooms for the table—or become an expert. It’s excellent advice, not because mushrooms are inherently difficult (some groups are, but many are not) but because they are unfamiliar. It’s harder to notice distinctions between unfamiliar things, meaning that mushrooms that look very different to an experienced forager may look all but identical to a novice. Even familiarity with a few favored species is sometimes not enough—there are documented fatalities among people whose families had been eating certain species for generations but then got poisoned by newly-introduced look-alike. Deep familiarity with mushrooms in general is simply safer—not to mention interesting!

Let me repeat, this list is an introductory guide and not to be used in place of a field guide, spore prints, or an identification app. It is even better if you can find a local expert in your area to help you in the field. If you go mushroom hunting make sure you take a quality knife with you and a basket/bag for your finds!

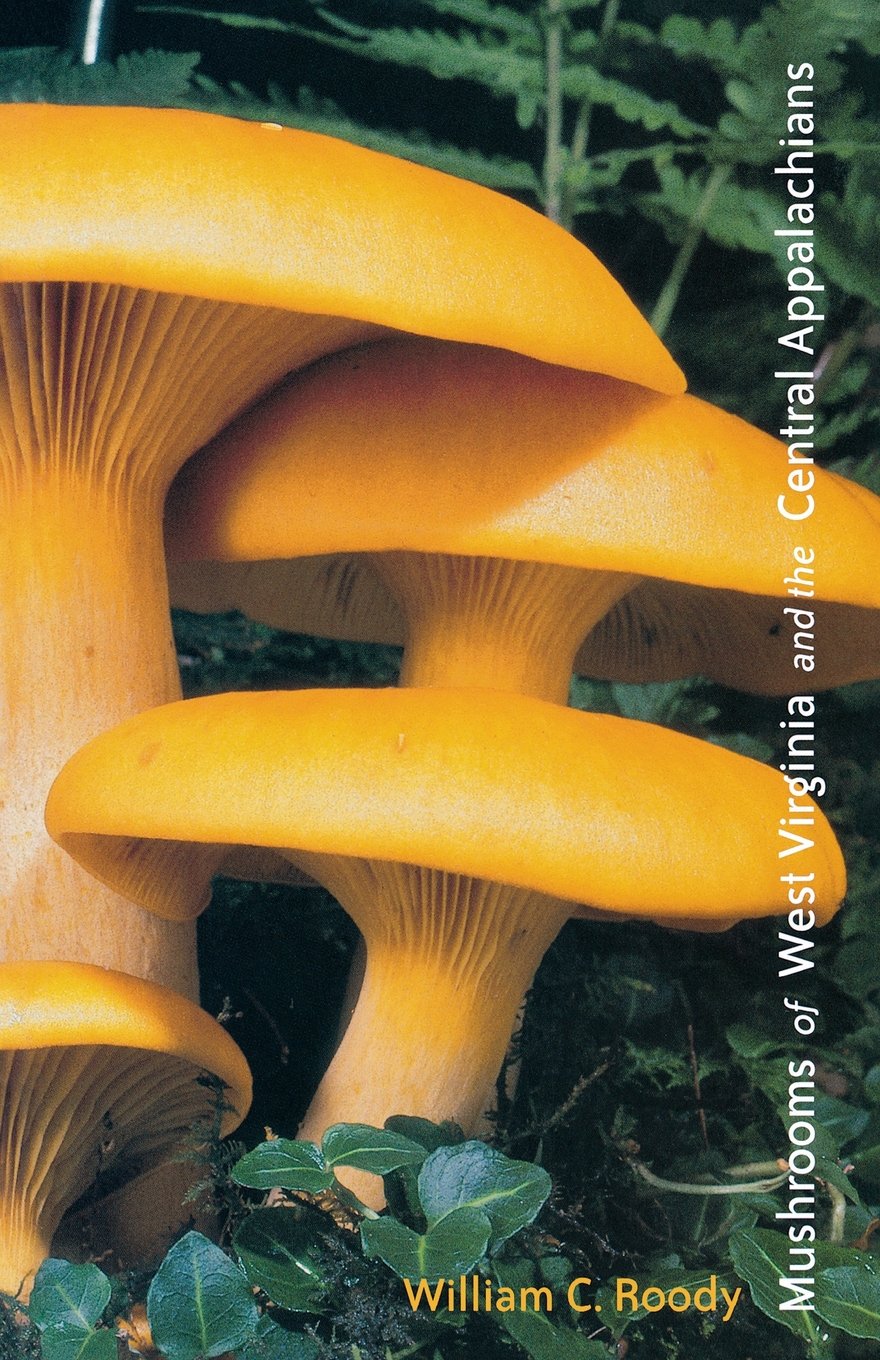

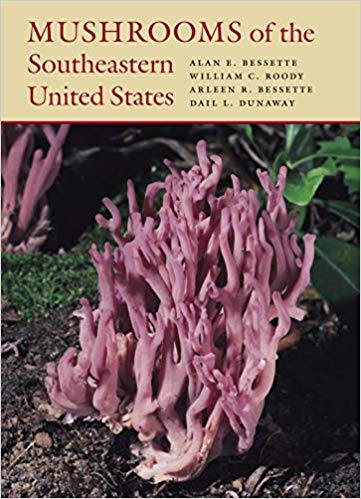

Our Recommended Field Guides for Virginia

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Edible Wild Mushrooms in Virginia

Morels (Morchella sp.)

The morels are a group of mushrooms so delicious that for some people they are the mushroom. All others simply don’t count. Their long, narrow, honeycombed caps and hollow stems are distinctive (watch out for look-alikes, though). Unfortunately, which morels actually live in Virginia is a difficult question.

Sources vary in the number of morels they say Virginia even has. Some think it has four or five: yellows, blacks, grays, and half-frees[ii]. Others claim three: black, yellow, and tulip[iii]. There is little confirmation on common names, which is a problem since morel taxonomy is difficult and confusing, to the point that multiple species share the same common name, while some single species have multiple common names. In fact, although Virginia’s Tulip Morel (as opposed to another species that lives farther west) is M. diminutiva[iv] and the North American half-free is M. populiphila “yellow” refers to a large group of species, as does “black.” And for gray morels, they are simply gray versions of other species[v].

It’s worth noting that morels of whatever species sometimes cause illness. It’s not entirely clear what makes the difference, although certainly they should never be eaten raw.

Chanterelles (Cantharellus) and Trumpets (Craterellus)

The Chanterelles are a large group of mostly choice edibles, all with a distinctive shape like the bell of a trumpet or perhaps a martini glass. There are no gills. Instead, the spores are released from ridges on the outer surface of the bell. In some species, there is, indeed, an inner surface, like the inside of a glass. Others are flat-topped or only slightly indented. Most are in the Cantharellus genus, but the similar and closely-related trumpets (Craterellus) are sometimes called chanterelles, as are some in other genera.

Virginia’s species include one of several species called the Black Trumpet (Craterellus cornucopioides, in this case), plus the Smooth Chanterelle (Cantharellus lateritius) and the Red Chanterelle (Cantharellus cinnabarinus), and the famously delicious Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius). That last is usually the one meant if somebody says “Chanterelle” and doesn’t specify.

There is also the False Chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca), which has at times been included in the Cantharellus genus and differs from the other members of the group only in that its ridges do not branch. Some people have hallucinated unexpectedly after eating it, and other unpleasant reactions may be possible, but its status as edible or toxic has not really been resolved yet. The main reason not to eat it is simply that it’s not very good.

Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus)

The Oyster Mushrooms are another large and delicious group, but this is the one people usually mean when they say “Oyster Mushroom” and don’t specify. It is whitish, somewhat shelf-like or fan-like in shape, and it eats and fruits from dead wood. The name, Oyster Mushroom, is probably a reference to their appearance, as they don’t taste like oysters—the taste is mildly “mushroomy,” sometimes delicately fragrant, with a soft, delicate texture.

There is some intriguing research suggesting that Oyster Mushroom may be useful medicinally, but as is usually the case with mushrooms, few studies have actually involved human subjects. It’s not clear yet whether Oyster Mushroom really works as medicine.

Witches’ Butter (Tremella mesenterica)

Witches’ butter is not a popular edible, but it’s too delightfully weird not to mention. The fruiting body takes the form of little yellow blobbies (there is a rare white form, too), looking less like butter and more like jelly. The fungus that grows these blobbies is parasitic on other fungi that decompose dead wood—because it feeds on the mycelium of its host, not the fruiting body, the host may be invisible. The common name “witches’ butter” refers to at least two species besides this one, but all three are edible, tasteless, and reportedly leave a tingling, cooling sensation on the tongue[vi].

Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus)

Lion’s mane is not especially leonine, but it’s legitimately mane-like, being covered all over with long, spine-like hairs. Under all the spines, it is club-shaped and fruits from trees, usually from a wound part-way up the trunk. Several closely-related and similarly-spiny species exist, but they branch. For some reason, some people treat all Hericium as interchangeable, referring to all of them as “Lion’s Mane” and recommending all of them in certain medicinal contexts—some interesting preliminary research suggests that H. erinaceus may indeed be useful medicinally, but the others have not yet been investigated.

What is known is that Lion’s Mane (and its spiny/hairy relatives, Ex. Hericium americanum) tastes good—rather like crab-meat. The spines don’t feel hairy in the mouth. Usually, they aren’t noticeable at all.

Parasol Mushroom (Macrolepiota sp.)

The Parasol[vii] is a large, choice edible, reportedly especially good as Parasol schnitzel. Plus, this species has the charming characteristic of being shaped like a lollipop when young—the un-expanded cap is spherical.

There is some confusion about this species, in that while it is usually referred to as either M. procera or M. prominens, but both are European species, and there’s no hard evidence that either occurs in North America. The North American population may well be made up of multiple un-named species[viii]. So the proper name of Virginia’s Parasol is not known.

The Parasol does have a number of poisonous look-alikes, most notably the shaggy parasol/false parasol group, which contains several specials that are toxic sometimes but not others. There are also a number of species collectively called Dapperlings (though the word “Parasol” is often in their individual names), that are very similar except for being smaller. There is overlap in size, so small Parasol specimens should not be eaten, just in case. Finally, Parasols do bear a vague resemblance to some deadly toxic Amanitas. Do not eat mushrooms without paying attention to identification.

Magic Mushrooms in Virginia

Virginia hosts an interesting range of psychoactive mushroom species. Most owe their activity primarily to Psilocybin, a substance that is certainly not risk-free to use (in rare cases, convulsions and even death can occur), but is usually relatively safe as long as users follow some common-sense precautions. It’s also extremely illegal, both at the Federal and state level. Getting caught with this substance (whether it’s in a mushroom or in a jar doesn’t matter, legally) can result in very serious prison time.

Following is a list of the psilocybin-containing mushroom species of Virginia[ix]. However, the state also hosts the Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria), a large and beautiful mushroom historically used for its psychoactive properties. It depends for its activity on a very different substance, and thus offers a qualitatively very different experience. Most mushroom-users these days seem to prefer psilocybin. But the other reason A. muscaria is less popular, besides that preference, is that unless this mushroom is processed properly, it is seriously toxic. Fatalities are rare but possible, and the experience is extremely unpleasant.

Please note that anyone who chooses to risk the law and gather psilocybin-containing mushrooms must be sure to positively identify every single specimen. These species have a deadly look-alike that sometimes even grows within clumps of the “shrooms.”

Gymnopilus

Only a few species in the Gymnopilus[x] genus are “active,” and they are rarely used, their effects are not well-known. Virginia has two species, G. luteus[xi] and G. luteofolius.

Panaeolus

Panaeolus mushrooms are notable for having spotted gills, since the spores mature and darken in patches, not all a once. Thus, they earn their collective common name, Mottlegills, though psychonauts tend to just call them pans. Not all are psychoactive—some authorities separate out the “active” members in their own genus, Copelandia. Virginia has two species. The Banded Mottlegill (P. cinctulus),[xii] has an outer cap margin of a different color than the center. It has very low potency, perhaps better suited to microdosing. In contrast, The Blue Meanie (P. cyanescens)[xiii] is extremely potent. It is also the subject of confusion around its name. Not only is “Blue Meanie” also the name of a cultivated variety of Psilocybe cubensis, but the species epithet, “Cyanescens,” also belongs to a third species, Psilocybe cyanescens. It’s important not to mix these three up, since dosing is different for each.

Psilocybe

Psilocybe is the genus for which psilocybin was named. One of its members, P. cubensis (which doesn’t seem to have a common name) is one of the most popular psychoactive species in the world and has many named and cultivated varieties. It does grow wild in Virginia, but only near the coast. Even there, it is rare. Two other species are present and more wide-spread, P. caerulipes[xiv] and P. ovoideocystidiata[xv]. Both share the common name “blue-foot.” The latter is the bigger one.

Poisonous Mushrooms in Virginia

The following list is my no means exhaustive—there are many poisonous species in the state not on the list—but it does explore some of the most dangerous.

Jack O’Lantern (Omphalotus illudens)

The Jack o’Lantern Mushroom[xvi] glows in the dark—though only very faintly. It’s hard to see. The species’ other claim to fame is that its bright orange color sometimes leads people to misidentify it as the delicious Golden Chanterelle, to which it bears a slight resemblance. Eating this poisonous look-alike is not usually deadly, but it’s bad enough.

Destroying Angel (Amanita sp.)

Destroying Angel isn’t a single species but a small group of nearly identical mushrooms (Amanita bisporigera, Amanita ocreata and Amanita virosa) within the Amanita genus . It’s hard to be sure which species Virginia has, but because all of them are deadly poisonous, most foragers don’t really need to know—the point is don’t eat this one! These angels are white or whitish with a white spore print. Mature specimens are sometimes mistaken for other white or whitish agarics, such as Meadow Mushroom or Parasol. Younger mushrooms may be mistaken for Ink Caps or Shaggy Mane. The young “egg” stage is a close look alike for several Puffball species[xvii].

Deathcap (Amanita phalloides)

Although not all Amanitas are poisonous, many of them are, to the point that some experts recommend never eating any Amanita, just in case. The Deathcap, at the name implies, is another deadly-poisonous species. It’s native to Europe but has spread over much of the rest of the world. It closely resembles the destroying angels, but usually has a greenish or brownish cap.

Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata)

The deadly galerina is one of the LBMs or “little brown mushrooms,” a large group of mostly unrelated species that are very difficult to tell apart. Some are good edibles, some are relatively safe psychoactives, and then there is the Deadly Galerina, which kills most of the people who eat it. It’s the same toxin as in some of the Amanitas, meaning the progression of symptoms includes a period where the patient appears to recover just before the liver and kidneys begin to fail. Deadly Galerina also sometimes grows within clumps of its edible look-alikes. Always ID every single mushroom before eating[xviii].

My name is Austin Collins.

I've dedicated my life to Mushrooms.

I believe Mushrooms are the best kept secret when it comes to health and well being.

For that reason, I would like to share a company with you that in my opinion makes the best mushroom products on the market.

The company is called Noomadic Herbals, my favorite supplement they make is called "Mushroom Total".

I take their products every day and they have helped me think better and have more energy. Give them a try.

-Austin

References:

[i] (n.d.). Lichens and Mushrooms of Virginia. iNaturalist

[ii] Gloria (2015). Morels. Virginia Wildflowers

[iii] Ingram, B. (2021). March Means Morels. Virginia DWR

[iv] Roehl, T. (2020). #226: Tulip Morels. Fungus Fact Friday

[v] (n.d.). Identifying Gray Morels. Hunt Mushrooms

[vi] Adamant, A. (2018). Foraging Witch’s Butter Mushroom. Practical Self-Reliance

[vii] (n.d.). Macrolepiota procera var. procera (Scop.) Singer—Parasol. First Nature

[viii] Kuo, M. (2015). Macrolepiota procera. MushroomExpert

[ix] (n.d.). Which Psilocybin Mushrooms Grow Wild in My Area? Shroomery

[x] (n.d.). Gymnopilus. Wikipedia

[xi] Kuo, M. (2012). Gymnopilus luteus. MushroomExpert

[xii] (n.d.). Panaeolus cunctulus. Philosophy

[xiii] Barlow, C. (2021). Blue Meanies Mushrooms: A Guide to the Potent Panaeolus cyanescens. Double Blind Magazine

[xiv] (n.d.). Psilocybe caerulipes. Philosophy

[xv] Roderick (2019). Psilocybe ovoideocystidiata. Psillow

[xvi] (n.d.). Omphalotus illudens (Schwein.) Bresinky & Besl—Jack o’Lantern. First Nature

[xvii] Illinois Department of Natural Resources (2021). Destroying Angel. Biodiversity of Illinois

[xviii] (n.d.). Galerna marginata. Illinois Mushrooms