West Virginia is the only US state entirely within Appalachia, with a varied ecology shaped by elevation changes and the history of human land use, such as mining. You would expect to find lots of mushrooms here, and you would be right. Here is a brief introduction to what the state has to offer[i][ii][iii][iv].

Foraging for edible mushrooms is a fascinating hobby, but not one for beginners to attempt alone—not that most mushrooms are especially difficult to identify, but it is a learned skill, and while most mushrooms are not poisonous, the consequences of accidentally eating one of the few exceptions can be dire. So the purpose of this list is not to get you started in foraging—it’s purpose is to give you reasons to develop the skill so you can go foraging.

If you do indeed go Mushroom Hunting make sure you have the proper tools, take a quality knife with you and a basket/bag for your haul!

This article is just some encouragement to help get you up that learning curve. This list is not meant to be used as a replacement for a field guide, spore prints, an identification app or an in person guide.

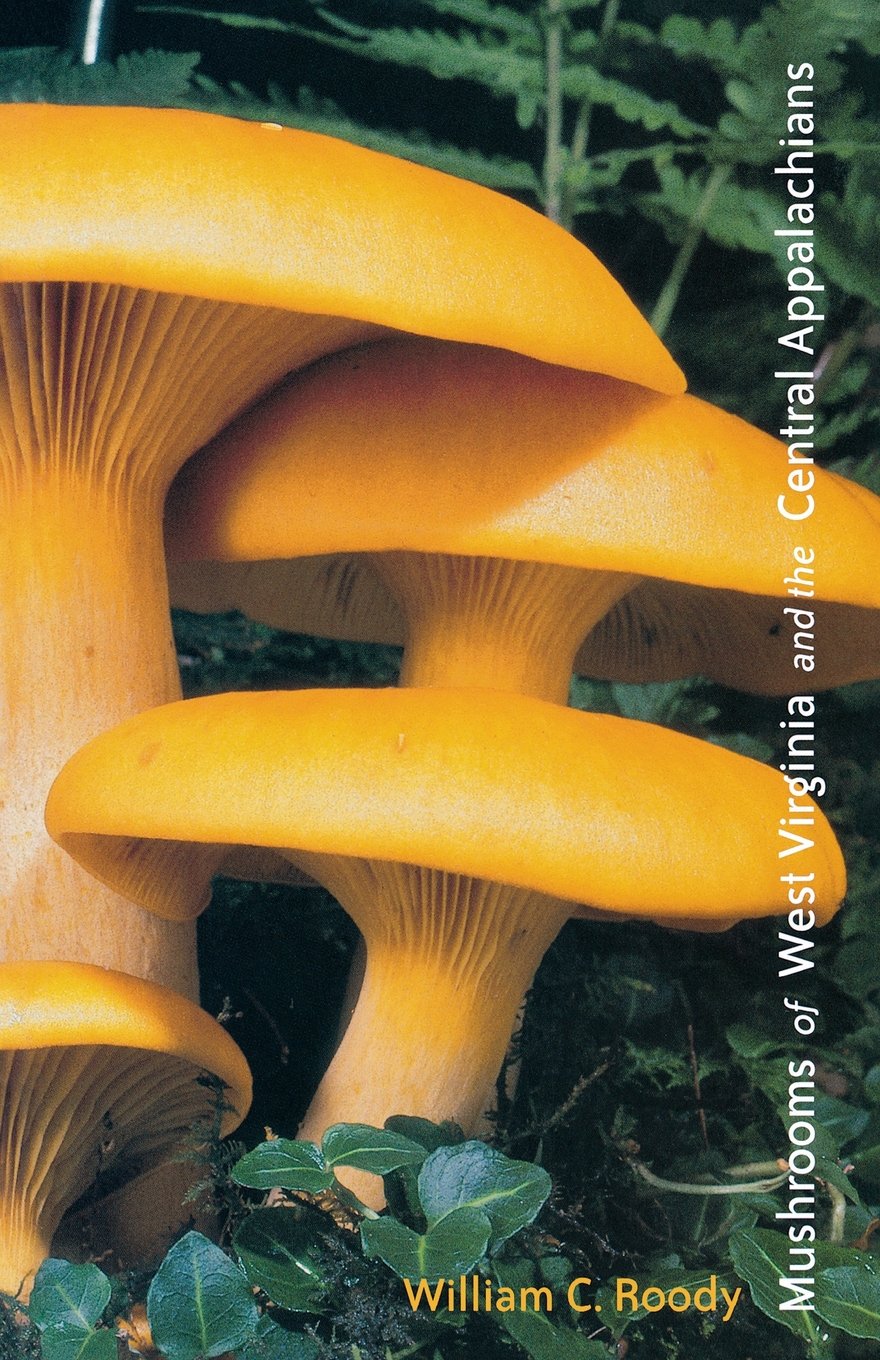

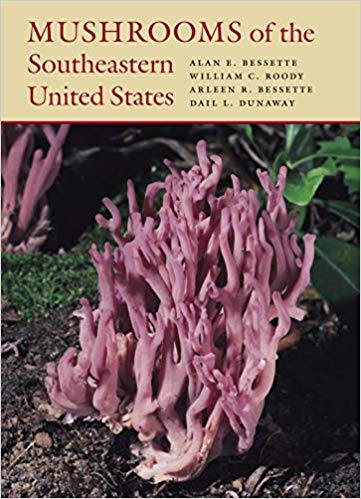

Our Recommended Field Guides for West Virginia

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Edible Mushrooms in West Virginia

Tawny Milkcap (Lactifluus volemus)

The Milkcaps are a group of mushrooms known for oozing liquid when sliced across the gills. Though this fluid is white in some cases, there are mushrooms with “milk” of other colors. Many (though not all!) Milkcaps are safe to eat, and the Tawny[v] is considered one of the best. Note that its scent, when fresh, is strong, distinctive, and not appetizing. That’s OK—the scent transforms into a mild nuttiness when cooked.

Frost’s Bolete (Exsudoporus frostii)

Frost’s Bolete[vi] is a perfect example of why the simple rules-of-thumb about poisonous mushrooms don’t work—according to the rules, this mushroom looks like it ought to be poisonous, but really it’s perfectly safe to eat. Its flavor is sour with a hint of bitterness, and is therefore probably best combined with other mushrooms rather than eaten alone. But it is a lovely bright red, or sometimes red and yellow, and an interesting addition to a meal. Just don’t confuse it with one of the real poisonous boletes!

Note that bolete taxonomy is confusing. A “bolete” is any parasol-shaped mushroom with pores rather than gills, and they all used to be lumped into the same genus. Since then, a lot more has been learned about these fungi, and while they do seem to all be related, they aren’t all closely related, and some seem to be given new scientific names every fifteen minutes. Don’t be surprised if you see Frost’s Bolete listed in several different genera, depending on which informational source you’re looking at.

Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus)

Lion’s mane is one of a very distinctive little group of fungi that are entirely covered with soft, hair-like spines. Lion’s mane is the only one that does not branch, so it looks rather a white or off-white tribble, from Star Trek. It eats dead or dying wood, and will fruit from wounds on infected trees year after year. The only species lion’s mane are likely to be confused with are other members of the same genus—and, fortunately, all are edible and taste remarkably like crab meat. Surprisingly, the spines don’t feel like anything in particular in the mouth.

Be aware that although many writers treat all the Hericiums as interchangeable, it is only the lion’s mane that has been researched for potential medicinal value. We simply don’t know whether its relatives have the same potential.

Wine-Cap Stropharia (Stropharia rugosoannulata)

The Wine-Cap Stropharia[vii] is a lovely burgundy color when young, and it often gets quite large. It’s also a popular edible, though it may be better known for its use as a biocontrol agent of nemotode worms—this is a predatory fungus that uses hunting as a way to supplement its rather nutrient-poor diet of dead wood. Turns out that the predatory habit is not unusual among wood-eating fungi, but hunting methods vary so much that it appears the behavior evolved independently several times. Wine-caps use microscopic spines on their underground hyphae as snares to immobilize and pierce the tiny worms.

Chicken-of-the-Woods (Laetiporus sp.)

Chicken-of-the-Woods, also known as Sulfur Shelf, is a group of similar-looking shelf-fungi that grow in shades of orange, yellow, pink, and sometimes white, depending on the species. West Virginia has at least two species, but it’s difficult to be sure which as these fungi used to be all lumped together in a single species, and many people continue to use the old scientific name for all of them.

The discovery that they are a group of species, not just one, may solve a puzzle that has long bothered foragers—occasionally chicken-of-the-woods, a well-known choice edible, makes people mildly ill (even when it’s cooked properly). Some are also tougher and less palatable than others. It may simply be that some species in the group are good to eat and some are not.

And yes, they do taste like chicken.

Morels (Morchella sp.)

The morels are a very popular group of edible fungi, widely considered among the best-tasting anywhere. Their distinctive appearance—the tall, narrow caps pitted like honeycomb—makes it fairly easy to determine that something is a morel. There are a few complications, of course.

One complication is that although most people find properly-cooked morels perfectly safe to eat, now and then someone gets sick. Nobody knows why. It’s best to eat them in moderation, especially at first. Another complication is that although it’s easy to tell that something is a morel, telling which morel you’ve got is harder—many morel species are highly variable, and many resemble them quite closely. The taxonomy was messed up for a long time, and still isn’t quite sorted out. Some species have more than one common name. Other common names belong to more than one species. West Virginia has at least three species: M. americana; M. angusticeps; M. populiphila (Formerly thought to be M. semilibera).

Chanterelles (Cantharellus)and Trumpets (Craterellus)

Chanterelles may be, next to morels, the most popular group of edible mushrooms. They vary, depending on species, from truly excellent to merely very good. They, too, are a distinctive group with a few complications. One complication is that some of them are trumpets, and vice versa. The two genera, Cantharellus and Craterellus, are very similar and closely related, and some species have been moved back and forth between the two, with resulting muddlement of common names. It doesn’t really matter, though, as both are edible and quite good. They can be treated as a single group.

Chanterelles/trumpets don’t exactly have a cap, and they don’t have gills. Instead, the stem simply widens out like the bell of a literal trumpet. Ridges or veins on the outside of the bell take the place of gills. Looking for those ridges or veins will eliminate most (though not quite all) look-alikes. So telling that something is a chanterelle or a trumpet. Telling which one it is may be harder.

For years, all the large, Yellow Chanterelles were subsumed into a single species, the Golden Chanterelle, widely considered among the best edible fungi there are. Now, the golden is known to be multiple species, except that a lot of writers still use the old name for all of them. West Virginia has at least one species in the Golden Chanterelle group.

Other West Virginia chants include the aptly-named Red Chanterelle (Cantharellus cinnabarinus), the yellow and brown yellowlegs (Craterellus tubaeformis), and the Black Trumpet (Craterellus fallax). Note that there are multiple black trumpet species, but this one is eastern North America’s.

Our Recommended Field Guides for West Virginia

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Poisonous Mushrooms in West Virginia

Most mushrooms are not poisonous, but there are some important exceptions. Unfortunately, there are no simple rules to tell you whether a mushroom is poisonous or not—any such rules you may encounter have exceptions, and following those rules could make you sick or even dead. You just have to learn to identify mushrooms to species and then look up whether the one you’ve got is poisonous or not. This list is by no means exhaustive—don’t assume something’s edible because you don’t see it on this list.

Please note that many species are poisonous sometimes but not all the time, and it’s not always clear what makes the difference. Toxin levels probably vary, and human susceptibility may vary, too. Then, too, some people have allergies. It’s best to be cautious when eating anything you haven’t eaten before.

Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera)

The Destroying Angels are a group of large, white or whitish, handsome mushrooms that will most likely kill anyone who eats them. Prompt medical treatment can save some, and, contrary to popular belief, organ transplants are not always necessary, but most poisoning victims don’t make it. No one eats destroying angel on purpose, but it’s occasionally mistaken for virtually any large, white edible mushrooms, even those it does not closely resemble. Apparently, the power of wishful thinking should not be underestimated.

A. bisporigera is West Virginia’s destroying angel. There are others. And while there are some members of the Amanita genus that are safe to eat, there are also other dangerously poisonous species in addition to the angels.

Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata)

Deadly Galerina, or Funeral Bell, contains the same poison as Destroying Angel, but it is much easier to mix up with edible species—it is a small, brown, nondescript mushroom, a description that also applies to multiple popular culinary species plus nearly all of the magics. And it even grows in mixed clumps with some of its lookalikes. Carefully identify every single mushroom headed towards a human mouth—every single one.

Many mushrooms, once thought to be a single species, turn out to be a group of species. Deadly galerina is the rare opposite. You may see it listed as Galerina autumnalis in older sources, a relic of a time when there were thought to be two Deadly Galerinas.

False Parasol (Chlorophyllum molybdites)

False parasol is not going to kill you you, but if you eat one you’ll wish you hadn’t. These are often mistaken for various edible white or whitish species, such as some of the Agarics, Shaggy Mane, and of course the Shaggy Parasols. In fact, the false parasol is only the most consistently poisonous of the shaggy parasol group, all of which are sometimes safe and sometimes not.

Jack O’Lantern (Omphalotus illudens)

The Jack o’Lantern mushroom is famous for three things, two of which are debatable. Supposedly it looks like the Golden Chanterelle, even though it is orange (not yellow) and has true gills (not ridges). Supposedly it glows in the dark, though many people have looked and failed to see the glow. Supposedly, you’ll get very sick if you eat it—and that last supposition is entirely correct. It’s poison.

There are other Jack o’Lantern species, and some writers still use the wrong scientific name for this one.

Yellow Stainer (Agaricus xanthodermus)

The Yellow Stainer[viii] is a close relative of the common domestic mushroom. As such, it is one one the few poisonous members of a mostly-edible group of very similar-looking species. And in fact, some people can eat it without trouble. Others spend the night indisposed. It’s not the only yellow-staining Agaricus, though its yellow is the brightest. Perhaps the best clue as to its identity is its scent of ink or iodine.

False Morel (Gyromitra esculenta)

The False Morels do resemble True Morels, although their caps are wrinkled rather than pitted, but that’s not why people eat them. These are not cases of miss-identification; some people simply insist that false morels are safely edible. We’ve listed them among the poisonous species, but those who eat false morels do have a point.

The issue is that False Morels, like True Morels, are toxic sometimes to some people, but not everybody. It’s a question of how much you want to risk. There are some false morel species that have low levels of toxin and, provided they are well-cooked in a well-ventilated kitchen (fumes from the cooking process can be toxic), are safe for most people most of the time. G. esculenta[ix] is the most toxic member of the group, though, and while many people do eat it, they probably shouldn’t. There is some evidence that the toxin is cumulative, meaning that you can eat these mushrooms without apparent ill effect for years and then suddenly get very sick as the toxin builds up.

False Chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca)

The False Chanterelle[x] does have gills, but its shape, size, and color are legitimately similar to that of some of the chanterelles. In fact, it was considered a member of the Cantharellus genus for a while. It certainly tastes bad, and has made a few people sick. It’s considered not worth the risk.

Woolly Chanterelle (Turbinellus floccosus)

This one is a close Chanterelle lookalike, hence the name, but the Woolly Chanterelle[xi] is not closely related to the true chants. Its outside is wrinkled rather than ridged or veined, and its scaly surface and woolly appearance are unlike any Chanterelle. Some people do eat them, but they have made a few people sick.

Our Recommended Field Guides for West Virginia

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Magic Mushrooms in West Virginia

Magic mushrooms are generally those that contain psilocybin, a psychoactive substance that is illegal to use or possess in most jurisdictions, though many people use and possess it anyway. It is one of the safer ways available to alter consciousness, but please remember that it’s use is not risk-free and could cost you your freedom besides.

There are psychoactive mushrooms whose activity depends on substances other than psilocybin, but they provide a qualitatively different kind of high and are much more dangerous. Here, we are only listing West Virginia’s psilocybin mushrooms[xii].

Psilocybe sp.

Psilocybe is the genus of what may be the post popular and best-known psilocybin mushroom in the world, Psilocybe cubensis, which does indeed grow in West Virginia, although it is rare in the state. More common are P. caerulipes and P. ovoideocystidiata, very similar-looking species that have been nicknamed little blue-foot and big blue-foot respectively.

Panaeolus cinctulus

The Panaeolus genus is a bit of a mixed bag, as some of its members are extremely potent ant others aren’t psychoactive at all. This very widespread species, which bears the common name, Banded Mottlegill, is close to the middle of the scale, being slightly less than medium potency.

Gymnopilus luteus

This species is part of a group of very similar, closely related mushrooms often called the Gymnopilus junonius group. They are known to be psychoactive, but it is difficult to get any information about their potency or effects.

References:

[i] (n.d.). Mushrooms of West Virginia. WVDNR Wildlife Resources Section

[ii] Vulpez, Evan (2021). Networking in the Forest: Mountain State Mushrooms. Highland Outdoors

[iii] Sept. J. D. (n.d.). Mushrooms of Appalachia. Quick Reference Publishing

[iv] Eddee (2009). Observation 29681: Galerina marginata. Mushroom Observer

[v] Bergo, A. (2022). Lactifluus volemus. Forage/Chef

[vi] Roehl, T. (2020). #220 Butyriboletus frosti. Fungus Fact Friday

[vii] (2018). Fungi Friday; Stropharia rugosoannulata. Forest Floor Narrative

[viii] (n.d.). Agaricus xanthodermus Genev.—Yellow Stainer. First Nature

[ix] Bergo, A. (2022). On Cooking False Morels/ Gyromitra. Forage/Chef

[x] (n.d.). Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca (Wulfen) Maire—False Chanterelle. First Nature

[xi] Wood, W., Stevens, F. (n.d.). California Fungi—Turbinellus floccosus. California Fungi

[xii] (n.d.). Which Psilocybin Mushrooms Grow Wild in My Area? Shroomery

Our Recommended Field Guides for West Virginia

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

I live right at the edge of the national forest and I am always on the look out for blue foots. I have seen quite a lot of little brown mushrooms that look like the pictures I see of blue foots, but I have noticed that even the documented pictures of them are DIFFERENT in some cases and virtually IDENTICAL to other harmful mushrooms. Being that I am NOT CRAZY, stupid, or desperate enough to actually eat ANY of the prime suspects I have found. I am truly and completely frustrated with the seemingly impossibility of 100% identification of these things. Where in the world do you gain the expertise and ability to PROPERLY identify these little brown mushrooms?

Hi Scott,

It’s all about experience and finding a trusted expert in your area. The field guides I recommend are a great resource, but LBM’s will always be a problem even for the most experienced!