New Jersey doesn’t get the credit it deserves as a place of natural wonders. Besides its miles of sand beaches, the state is home to the forests and streams of the Pine Barrens and a small but lovely corner of the Appalachian Mountains. And all of it has mushrooms[i].

This article should not be taken as a guide for foraging. To begin foraging based on articles found on-line is, in fact, a very effective means to end up poisoned. The world of mushrooms is vast and intricate, and navigating it requires real expertise earned through serious study over a long time.

This article is part of our effort to convince you that the time and study is worth it.

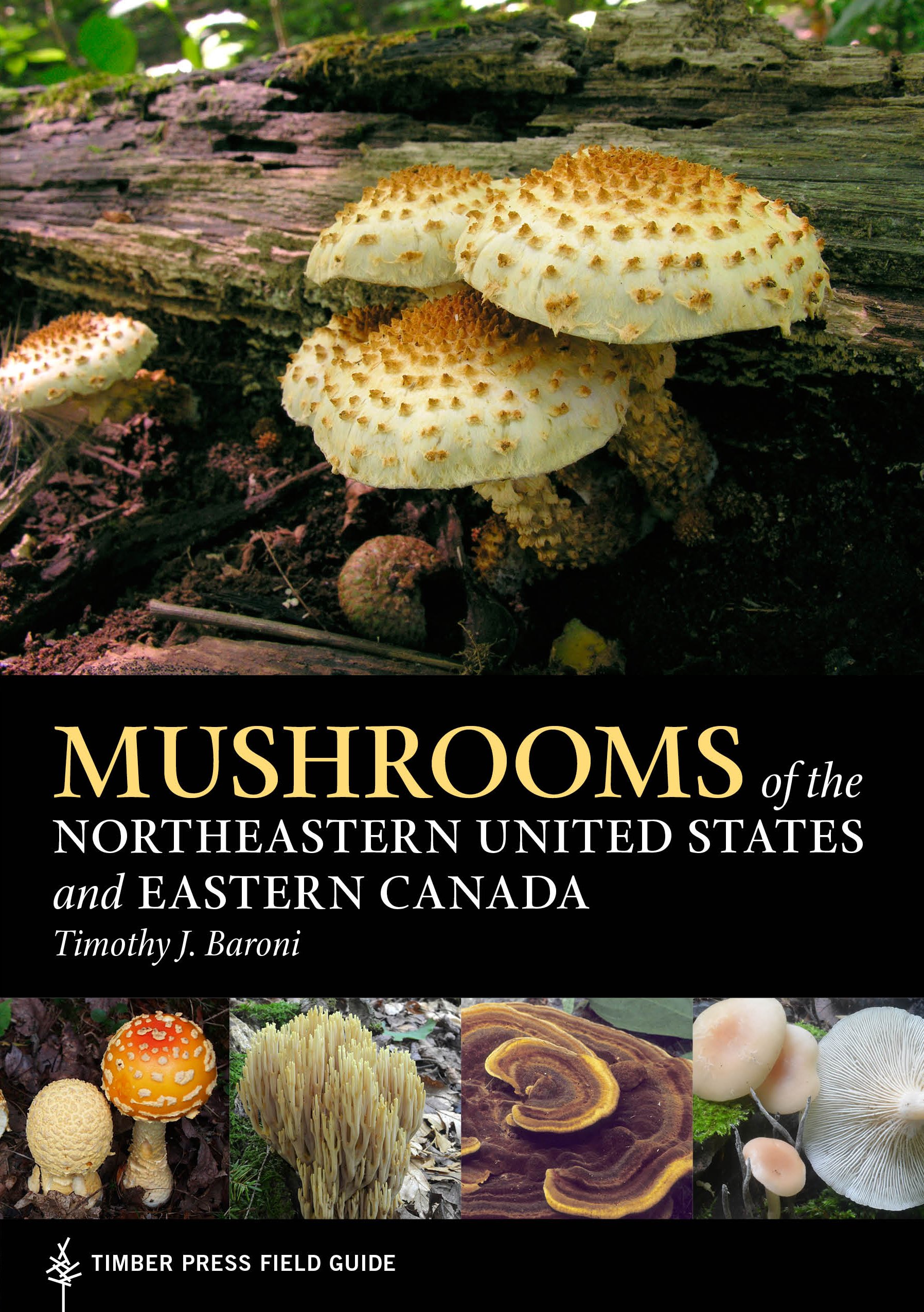

Our Recommended Field Guides for New Jersey

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Edible Wild Mushrooms in New Jersey

It’s easy to find lists online of fool-proof, easy-to-identify mushrooms for beginning foragers. There is no such thing—there is no substitute for real expertise. In fact, such lists usually include worrying caveats, suggesting the listed mushrooms are not so easy after all.

And yet, identifying mushrooms is not as difficult as all these dire-but-necessary warnings may imply. It simply requires careful attention to a lot of details most of us aren’t otherwise used to thinking about, plus a working knowledge of a complex and ever-changing field. In other words, there is a steep learning-curve which any would-be forager absolutely must ascend, but once you get up there, moving about won’t be difficult.

If you do indeed go Mushroom Hunting make sure you have the proper tools, take a quality knife with you and a basket/bag for your haul!

This list is not meant to be used as a replacement for a field guide, spore prints, an identification app or an in person guide.

Here are a few of the mushrooms you can find in New Jersey once you do learn how to look.

Honey Mushroom (Armillaria mellea)

Honey mushrooms are a small group of similar species known for killing trees (a single fungal individual can attack multiple trees, using thick, black rhizomorphs to bridge the gaps between plants) and for producing large clusters of honey-colored mushrooms. In recent years, the taxonomy in the group has gotten very convoluted, with many more or less identical-looking species discovered through mating studies[ii]. A. mellea is the species listed for New Jersey, but the picture could be more complicated than it appears.

Honey mushrooms are widely considered a choice edible, yet make some people sick[iii]. Although it is generally supposed that some kind of hypersensitivity or allergy is responsible for the illnesses, the fact that it’s hard to tell one honey from another may also be relevant—perhaps one of their number is toxic? Honeys also have a deadly look-alike that shares the same growth habit and could fruit near or within honey mushroom clusters.

Armillarias have an interesting relationship with the aborting entoloma[iv]. See below.

Aborting Entoloma (Entoloma abortivum)

Here we have a confusing case where many guidebooks are seriously wrong.

E. abortivum is a non-descript gilled mushroom that is edible and quite tasty, but has some seriously poisonous look-alikes. It often (but not always) fruits in company with twisted-up things that look a bit like popcorn. For years, mycologists assumed that these popcorn-looking things were entolomas that had somehow aborted themselves—that the fruiting bodies didn’t fully develop—and so the name, Entoloma abortivum, was applied to both the typically-developed fruiting bodies and the presumed abortive form.

Then it was discovered that the popcorn-thingies contain both Entoloma and Armillaria hyphae, so mycologists assumed that the Armillaria was parasitising the Entoloma, causing the victim’s fruiting bodies to form strangely. That is the way the story is told in many field-guides, and the popcorn-things are almost universally discussed as Entolomas. They aren’t.

Actually, the popcorn-things are Armillaria fruiting bodies that form strangely because of their interaction with the Entoloma mycelium![v] It’s thought that the Entoloma is a parasite, but that hasn’t been confirmed—the nature of the relationship between the two fungi is not clear.

What is clear is that the popcorn-things are edible and taste like honey mushrooms (though with an altered, shrimp-like texture)–and the presence of the aborted Armillarias in an Entoloma patch is an excellent indication that this is indeed the edible aborting entoloma and not some other Entoloma that might not be good to eat at all[vi].

Chicken-of-the-Woods (Laetiporus sp.)

Chicken-of-the-woods, named for its chicken-like taste, is well-known as an easy-to-recognize, reliably safe, wild edible. Actually, it’s neither easy to recognize nor reliably safe.

It turns out there is a whole flock of chicken species, not just one—which may partially explain why some people get ill after eating this fungus, while others do not[vii]. Many writers still treat all chicken mushrooms as the same but warn foragers off eating chickens harvested from this or that tree species, assuming that toxins from the wood get into the mushroom. More likely, some chicken species are slightly toxic and become more so with age, and human sensitivity to the toxin varies. Unfortunately, it’s not yet clear which chickens are better for eating. The taxonomy of the group is still in flux[viii]. The best bet is to eat only young, well-cooked chickens, to taste in moderation until you know how you react, and to pay attention to which species you’re trying so far as you are able.

Note that “chicken-of-the-woods” is not the same as “hen-of-the-woods.” The two don’t especially look alike, it’s just that both remind some people of the same bird.

Puffballs

Puffballs all look roughly similar, being ball-shaped, but they aren’t related to each other[ix]. Most are edible when young, before the spores begin to develop—the exception are those called Earthballs, which are fairly distinctive within the group. The major caveat with the puffballs (other than avoiding earthballs) is that they look a lot like the immature “egg” stage of the deadly Amanitas. Any puffball headed for the table must be sliced vertically, not only to make sure the spores have not started developing, but also to look for the telltale “T” shape of a young Amanita.

New Jersey has at least two puffball species: the Stump Puffball (Apioperdon pyriforme) and the Common or Gem-Studded Puffball (Lycoperdon perlatum). Both are small with short, thick stalks.

Wood Blewit (Lepista nuda)

The wood blewit[x] is indeed blew—er, blue—at least when young. By maturity, the cap turns brown, but the stem and gills remain bluish. The mushrooms have a pleasant, anise-like flavor and are popular in Europe, although some people do react badly to eating them. Unfortunately, this species also has some very poisonous look-alikes.

Curiously, the wood blewit can also be used to make a green (not blue) dye.

Witches’ Butter (Tremella mesenterica)

This species[xi] looks a good deal more like lemon marmalade than butter. The texture is rubbery. The shape can best be described as “a globbie.” It is one of three species that bear the name “witches’ butter,” and, like the others, it is edible—it doesn’t taste like much but does make the tongue tingle nicely. It fruits from decaying wood, although this fungus doesn’t eat wood. Rather, it eats the fungi that do eat wood.

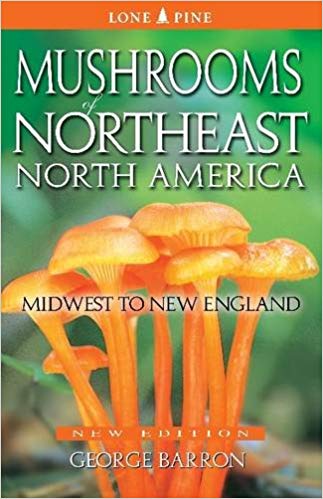

Our Recommended Field Guides for New Jersey

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Poisonous Mushrooms in New Jersey

The following list is not anywhere near exhaustive—neither was the list of edible New Jersey fungi. The point is please don’t assume that a mushroom is edible just because it’s not listed here among the poisonous species.

Eastern Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera)

New Jersey has a number of Amanita species, some of which are safe to eat—but it also has the destroying angel. Actually, there are several destroying angel, all of them large, handsome, all-white or whitish, and all likely to kill anybody who eats one. This is simply the one common in the Eastern US[xii]. Reportedly, they taste excellent, and the toxin takes a long time to take effect, sometimes a day or more, complicating diagnosis. Proper diagnosis is critical, because with amatoxin (the relevant group of poisonous substances), when the symptoms go away it is a sign that major organ failure is immanent. With proper treatment, some (not all) poisoning victims survive.

Although the Destroying Angel looks very distinctive, it is occasionally mistaken for almost every edible white mushroom around, even by experts. Attention to detail is critical.

Death-Cap (Amanita phalloides)

The Death-Cap[xiii] also contains a potentially lethal dose of amatoxin. It is about the same shape and size as the destroying angel, but it has a greenish-brown cap. It’s not native to North America but has been accidentally introduced, and there is an infestation in New Jersey[xiv]. It is often eaten by recent arrivals from Southeast Asia, as it resembles an edible mushroom popular in those countries. Other people (or their pet dogs) might try it simply out of curiosity. The death-cap is a good example of why learning to recognize just a few favorite edibles isn’t good enough—you have to know mushrooms well enough that you can tell the difference between a familiar species and a look-alike you didn’t know existed.

Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata)

Not all of the mushrooms that contain deadly amatoxin are Amanitas. The well-named Deadly Galerina[xv] is a case in point[xvi]. It is not just a close look-alike of many edible and psychoactive species, it also shares the same growth habit as some of these and can fruit in a cluster of some sought-after species. Never assume that just because one mushroom in a cluster is safe to eat that all of them are. Identify every single mushroom before eating.

Russula sp.

Not all poisonous mushrooms cause death. The Sickener usually just makes victims puke[xvii]. But the sickener isn’t one species. Instead, the name applies to any of a group of closely-related, pretty, red-and-white mushrooms whose taxonomy is a complete and utter mess[xviii]. Unless you are an accomplished expert whose life has not been sufficiently stressful lately, it’s best to abandon all hope of identification-to-species in this case and just call it the sickener.

False Parasol (Chlorophyllum molybdites)

This mushroom is the most toxic of a small group of similar species that range from usually (not always) poisonous to usually (and perhaps not always) safe. It’s also the only one of the group that consistently has green spores—though at least one of the others has green spores sometimes. This is not a simple case of the edible “true parasols” and their false and toxic look-alike. It doesn’t help the confusion that most members of the group are sometimes called “shaggy parasol,” after the rough texture of the top of the cap. These are large, handsome mushrooms, whitish in color—not only is the false parasol poisonous in its own right, it could also easily be mixed up with the deadly destroying angel (or, in some areas, with the also-deadly, but smaller, dapperlings[xix]).

Sulfur Tuft (Hypholoma fasciculare)

The sulfur tuft[xx] is a pretty little yellowish mushroom that often fruits in dense clusters. Eating it can result in gastrointestinal upset, temporary paralysis and vision problems, and possibly even death. Apparently some people claim that it is safe to eat anyway, though why anyone would bother isn’t clear—reportedly, the sulfur tuft tastes terrible.

Earthballs (Scleroderma sp.)

New Jersey has two very similar species of earthball—these are firm, thick-skinned puffballs that make eaters miserably ill. The most dramatic difference between these and edible puffballs of similar size is that the interior turns dark much earlier, but not so early that confusion is not possible. More reliable is their firmness, as the edible puffs are marshmallowy.

Our Recommended Field Guides for New Jersey

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Magic Mushrooms in New Jersey

New Jersey has at least five or six species of psilocybin-containing mushroom growing wild[xxi]. There are several reasons to be very careful about these, not least because picking and eating them is illegal—at the state level, it’s not as illegal as it used to be, since possible penalties have been dramatically lessened[xxii], but users can still go to jail, and the Federal ban is unchanged. Perhaps more importantly, all these species have a dangerous look-alike in the deadly galerina. People have died from eating what they thought were magic mushrooms but weren’t.

There are plenty of people who consider psilocybin well worth the risk, though.

New Jersey is also home to the iconic fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), though the local variety usually has a yellow cap, not a red one. This species is also known for its “magic,” but is biochemically very different from the psilocybes and is dangerously toxic unless processed exactly the right way.

Panaeolus

New Jersey has at least one member of the Panaeolus[xxiii] genus, a group known in English as the mottlegills because the spores develop and darken unevenly. Potency varies dramatically within the group, from intensely “active” species to some that are not psychoactive at all. New Jersey’s species, the Banded Mottlegill (P. cinctulus)[xxiv] is active but weakly so.

Psilocybe

The famous Psilocybe cubensis does not grow in New Jersey except in well-hidden indoor gardens (it is widely and enthusiastically cultivated), but three other members of the genus do. One, the very rare P. graveolens, was even discovered in New Jersey, in Hackensack[xxv]. The two others, P. caerulipes and P. ovoideocystidiata, share the common name of blue-foot—the latter is distinctly larger, but they are otherwise similar (not identical) and have a similar degree of potency (low-moderate).

Gymnopilus

The Gymnopilus genus taxonomically confused at present, so it’s difficult to say which species New Jersey has. In any case, the “gyms” are not well-known among psychonauts. The few published trip reports suggest its high is qualitatively different from that of the Psilocybes and the Panaeolus species most “magic” users are familiar with[xxvi].

References:

[i] (n.d.). Common Fungi of New Jersey: Compiled from Records of the New Jersey Mycological Association 1981-2019. New Jersey Mycological Association

[ii] Kuo, M. (2017). Armillaria mellea. MushroomExpert

[iii] (n.d.). Armillaria mellea (Vahl) P. Kumm. –Honey Fungus. First Nature

[iv] Kuo, M. (2014). Entoloma abortivum. MushroomExpert

[v] Volk, T. (2006). Entoloma abortivum, the Aborting Entoloma, AKA Hunter’s Heart, Totlcoxcatl, or “Ground Prunes.” Tom’s Fungi

[vi] Bergo, A. (n.d.). Shrimp of the Woods: Aborted Entoloma Mushrooms.

[vii] (n.d.). Laetiporus conifericola—Conifer Sulpher Shelf. Beaty Biodiversity Museum

[viii] Kuo, M. (2017). Laetiporus sulphureus. MushroomExpert

[ix] Kuo, M. (2008). Puffballs. MushroomExpert

[x] (n.d.). Lepista nuda (Bull.) Cooke. –Wood Blewit. First Nature

[xi] Adamant, A. (2018). Foraging Witch’s Butter Mushrooms. Practical Self-Reliance

[xii] (n.d.). Amanita bisporigera. Amanitaceae.org

[xiii] Childs, C. (2019). Death-Cap Mushrooms Are Spreading Across North America. The Atlantic

[xiv] Fischer, D.W. (n.d.). The Death Cap: Amanita phalloides: The World’s Most Dangerous Mushroom. American Mushrooms

[xv] (n.d.). Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata (Batsch) Kühner 1935. Maryland Biodiversity Project

[xvi] (n.d.). Galerina marginata (Batsch) Kühner—Funeral Bell. First Nature

[xvii] (n.d.). Russula emetica (Schaeff.)Pers.—The Sickener. First Nature

[xviii] Kuo, M. (2009). The Genus Russula. MushroomExpert

[xix] (n.d.). Lepiota subincarnata J.E. Lange—Fatal Dapperling. First Nature

[xx] (n.d.). Hypholoma fasciculare (Hids.) P. Kumm—Sulphur Tuft. First Nature

[xxi] (n.d.). Which Psilocybin Mushrooms Grow Wild in My Area? Shroomery

[xxii] Walsh, J. (2021). New Jersey Becomes Latest State to Loosen Penalties for Magic Mushrooms. Forbes

[xxiii] (n.d.). Panaeolus. Wikipedia

[xxiv] (n.d.). Panaeolus cunctulus. Philosophy

[xxv] (n.d.). Psilocybe graveolens. Wikipedia

[xxvi] Psycho Gnome (2014). Gymnopolus luteus found in Wisconsin (With Trip Report). Shroomery