Connecticut is a relatively small state, but it is geographically diverse, including mountains and beaches and forests. Of course it has a fascinating diversity of mushrooms as well, and while we can’t list everything, we can introduce you to a few of the more interesting species[i][ii].

The internet is full of articles designed to help beginning foragers get out in the field and start foraging. This isn’t one of those articles. Beginners should not forage for the table alone. It’s not that mushroom identification is some horrible, impossible task, it isn’t (unless you’re trying to identify Russulas), it’s just that knowing which details are likely to be important takes practice, so beginners are more likely to make mistakes. There’s a bit of a learning curve.

If you do indeed go Mushroom Hunting make sure you have the proper tools, take a quality knife with you and a basket/bag for your haul!

This list is not meant to be used as a replacement for a field guide, spore prints, an identification app or an in person guide.

This article is to show you why you might want to climb up that curve.

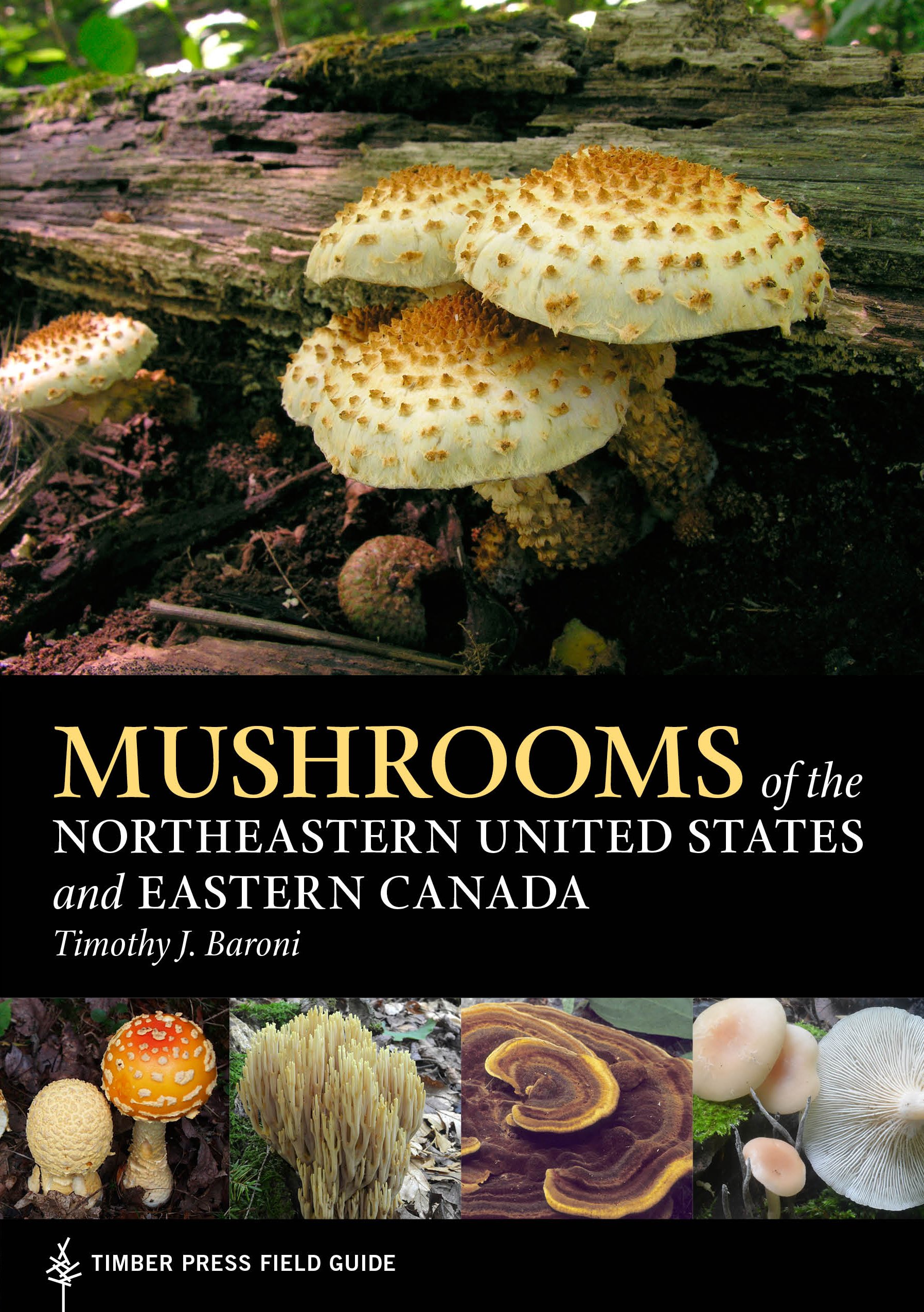

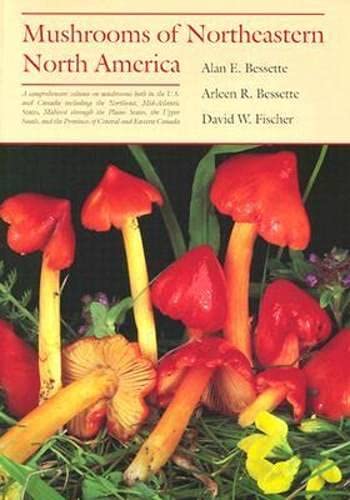

Our Recommended Field Guides for Connecticut

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Edible Mushrooms in Connecticut

Chanterelles (Cantharellus)

The Chanterelles, as a group, are famously delicious mushrooms—they are also very distinctive-looking, since they have ridges or veins in place of gills. They do have some inedible look-alikes, though. Connecticut has at least two species, the little Red Chanterelle (C. cinnabarinus) and a species of Golden Chanterelle—unfortunately, there are multiple golden chants, and it’s a little hard to be sure which one this state has.

Chicken-of-the-Woods (Laetiporus sp.)

Chicken-of-the-woods is a shelf-shaped mushroom in shades of yellow and orange. Reportedly, it does taste like chicken. It’s often listed as good for beginner-foragers on the grounds that it has no close look-alikes. Unfortunately, that’s not quite true. In fact, what we used to think of as a single species is actually a whole flock of them. Some are excellent as table-fare, some are ho-hum, and some are mildly poisonous. Geographic location and the species of tree the chicken is fruiting from are usually good clues as to identity, but it’s hard to find good information on which chicken(s) Connecticut actually has. Most sources simply list it under the old name from when we thought they were all the same.

Boletes

The boletes are a group united by sharing two features: a flat surface of pores, rather than gills, and an umbrella-like shape. At one time, they were all united under the genus, Boletus. Since then, many have been reassigned, and some have actually been reassigned multiple times over the past ten years—finding information about these mushrooms is difficult because every site seems to use a different name for the same species, depending on how up-to-date its information is. To avoid adding to the confusion, we’ll leave scientific names off entirely. In any case, most boletes are edible, though there are some important exceptions.

Connecticut’s edible boletes include Old-Man-of-the-Woods[iii], which often looks like an old pine-cone and tastes OK; the Red-Cracking Bolete (Xerocomellus chrysenteron)[iv], which is reportedly slightly too soggy to be enjoyable; Frost’s Bolete (Exsudoporus frostii)[v], with an interesting, slightly sour flavor; Pallid Bolete (Boletus pallidus)[vi], which is indeed pallid-looking and one of the better edibles out there; and the Bicolor Bolete[vii], which is red and yellow, may or may not smell like curry[viii], and pairs well with red meat.

Lobster

Lobster Mushroom isn’t exactly a mushroom; it’s what happens when a certain orange mold (Hypomyces lactifluorum) attacks a mushroom in either of two genera, Lactarius and Russula[ix]. The mold deforms its victims, preventing them from releasing their own spores, and giving them a characteristic “look.” It’s easy to identify a lobster—it’s hard to figure out what species the victim is, because they all end up looking the same. And curiously, although some members of both victim-genera are poisonous, lobster mushroom is always edible and always tastes about the same (a little like lobster, actually)[x].

Jelly Ear (Auricularia sp.)

The jelly ear[xi] is another species—or, rather, group of species—that used to share its scientific name with a fungus in Europe, until mycologists realized they aren’t the same thing. It’s not clear which of the three American species live in Connecticut. Regardless of which scientific name is correct, the common name is apt; these have an irregular, variable shape that often does look startlingly like a human ear. They’re also edible. They have little in the way of taste, but the interesting texture can be a fun addition to soups[xii]

American Caesar’s Mushroom (Amanita sp.)

The Amanita genus is justifiably famous for including the most dangerously poisonous mushrooms in the world, but it also includes several safely edible species, several of which grow wild in Connecticut. One of these is a species in the Caesar’s mushroom group, which are almost impossible to differentiate from each other but are collectively fairly distinctive—the combination of smooth, red or orange cap and yellow stem and gills stands out. That being said, even a small chance of confusion with its deadly relatives (or even with its not deadly but still dangerously toxic relatives) is so scary that many people advise not eating Caesar’s mushrooms at all. Your call, just don’t get poisoned.

Poisonous Mushrooms in Connecticut

Don’t believe anyone who tells you how to tell if a mushroom is poisonous. All the rules and tricks have exceptions. The only way is to find out what kind of mushroom it is and then look it up.

It’s worth noting that there are a lot of mushrooms that are safe to eat sometimes but at other times make people ill. Usually we can figure out why—some species are safe only if well-cooked, or when very young, or when not taken with alcohol, and so on. But sometimes nobody’s really sure. In these cases, some people decide the mushroom is poisonous (with some exceptions), while others decide it’s safe (with some exceptions). There’s definitely some risk assessment that goes on here.

Destroying Angel (Amanita Bisporigera)

And here we have one of the Amanita that can actually kill you. There are several destroying angel species (plus various non-angel deadlies), all of them large, white or whitish, and handsome, but this one is Connecticut’s. The toxin in this group is especially dangerous in that it can take a day or more after ingestion for symptoms to develop, making diagnosis difficult. It causes severe gastrointestinal problems for several days, but then these symptoms clear up—right before the patient’s liver and possibly kidneys fail. Prompt treatment by doctors familiar with amotoxin poisoning can save at least some victims.

Not surprisingly, nobody eats destroying angel on purpose, but it’s often mistaken for virtually any large, white, edible mushroom within its range. The distinguishing features of the species would seem very clear, but mistakes are easier to make than anyone expects. Mistaking a deadly Amanita for a safe and friendly agaric or inky cap is probably one of those “I never thought it would happen to me” things. But yes, it could happen to you. Be careful.

Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria)

This lovely mushroom (it really is good-looking) has become so iconic that if people who know nothing about fungi imagine a mushroom, it will probably be this one. It’s the one with a red cap and white spots (actually warts). The reason this species is famous is that it’s psychoactive and has a long history of ritual use in Europe—and is therefore culturally associated with fairies. The reason we’re listing it among the poisonous mushrooms today is that in addition to altering your mind, it can also make you very, very ill, if it’s not processed properly first. The chance of somebody making a mistake during processing and getting sick is very real and demands respect.

Of course, psychoactivity could itself be dangerous if the eater didn’t expect it and wasn’t prepared.

Earthballs (Scleroderma sp.)

The Earthballs are a group of poisonous puffballs—they aren’t the only poisonous puffballs, but since most puffballs are edible, the earthballs could offer someone a nasty surprise. They differ from the edible puffballs in several respects, but the best field-mark is probably that they are much more firm, less like a marshmallow and more like a rubber ball. They aren’t deadly, but will make an eater very sick. Connecticut has two species, the Common Earthball (S. citrinum) and the Onion Earthball (S. cepa).

The Sickener (Russula sp.)

Russula taxonomy is a mess even by the standards of modern mycology[xiii]. Many species are vaguely defined according to variable or even subjective characteristics and are difficult or even impossible to identify in the field—or, possibly, at all. And it’s quite likely that genetic studies will reorganize the whole thing. It’s a frustrating situation because Russulas are fairly large and often dramatically colored, and it would be really nice to know which one you’re looking at. But it is what it is. Let it be enough to know it’s a red-capped Russula or a green-capped one or whatever else. And call all the red-capped ones “the sickener,” since they’ll probably make you puke if you eat one.

Magic Mushrooms in Connecticut

Psychoactive mushrooms are not legal to possess in Connecticut, no[xiv]. Or, more precisely, possession or use of psilocybin (whether inside a mushroom or not) is against both state and Federal law. Penalties can be severe. Please do not get arrested.

Several of these mushrooms do grow wild in the state[xv]. Using them is, aside from legal risk, relatively safe, provided the user knows what they’re doing and takes standard precautions. Foraging wild magic mushrooms is a bit riskier, as they all have a close look-alike that could easily kill the unwary. Identify each mushroom to the species level before considering eating it, always.

Gymnopilus

This genus contains several psychoactive species, but as usual it’s hard to tell which ones are which since the taxonomy is in flux. Gyms aren’t commonly used, so there isn’t a lot of published information on what using them is like. They do contain psilocybin, but reportedly they produce a high that is qualitatively a little different that that of the more popular Psilocybes and Panaeolus.

Panaeolus cinctulus

The pans, or mottlegills, include a spectrum of psychoactivity, from totally inactive species all the way to some extremely potent mushrooms. This one, the banded mottlegill (though psychonauts tend to use only scientific names), is about in the middle.

The Bluefoots

There are two Connecticut Psilocybes that both have a bluish stem and differ mostly in size and typical fruiting season. They both provide a high very similar to that of their famous relative, Psilocybe cubensis (which prefers a warmer climate than Connecticut has) but they are slightly less potent. People who want to avoid causing confusion call them Little Bluefoot (P. caerulipes) and Big Bluefoot (P. ovoideocystidiata). Everybody else just calls both of them Bluefoot.

Our Recommended Field Guides for Connecticut

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

References:

[i] (n.d.). Fungi of Storrs (CT). iNaturalist

[ii] Malcom, S. (n.d.). Along the Air Line…Mushrooms. Performance Vision

[iii] (n.d.). Strobilomyces strobilaceus (Scop.). –Old Man of the Woods. First Nature

[iv] (n.d.). Xerocomellus chrysenteron (Bull.) Šutara. –Red Cracking Bolete. First Nature

[v] Roehl, T. (2020). #220: Butyriboletus frostii. Fungus Fact Friday

[vi] Bergo, A.(n.d.). Boletus pallidus. Forager/Chef

[vii] Von Frank, A. (2020). Bicolor Bolete (Baorangia bicolor)–How to Find, ID, and Eat This Wild Gourmet Mushroom. Tyrant Farms

[viii] Kuo, M. (2015). Boletus bicolor. MushroomExpert

[ix] Kuo, M. (2003). Hypomyces lactifluorum. The MushroomExpert

[x] Bergo, A. (n.d.). Lobster Mushrooms. Forager/Chef

[xi] Kuo, M. (2018). Auricularia “americana.” The MushroomExpert

[xii] (n.d.). Auricularia auricula-judae (Bull.) Wettst. –Jelly Ear Fungus. First Nature

[xiii] Kuo, M. (2009). The Genus Russula. MushroomExpert

[xiv] Dubley, P. (2022). Are Psychedelics Legal in Connecticut? Tripsitter

[xv] (n.d.). Which Psilocybin Mushroom Grow Wild in My Area? Shroomery