California, being a very long, relatively skinny state, naturally includes more than one kind of nature; specifically, there is Northern California and Southern California, and the two don’t have a lot in common ecologically. As a result, Californians get at least two different kinds of mushroom country for the price of one. In general, the northern part of the state has more species than the southern part does, but there are a few that prefer the south, and a good number that grow all over.

There are way too many mushroom species in the state to name all of them. The following is just a small sampling. Please remember this list is merely educational and not to be used in place of a field guide, spore prints, or an identification app. Even more preferable is an expert to guide. you in person. If you do end up going out mushroom hunting make sure you take a quality knife with you and a basket/bag for your finds!

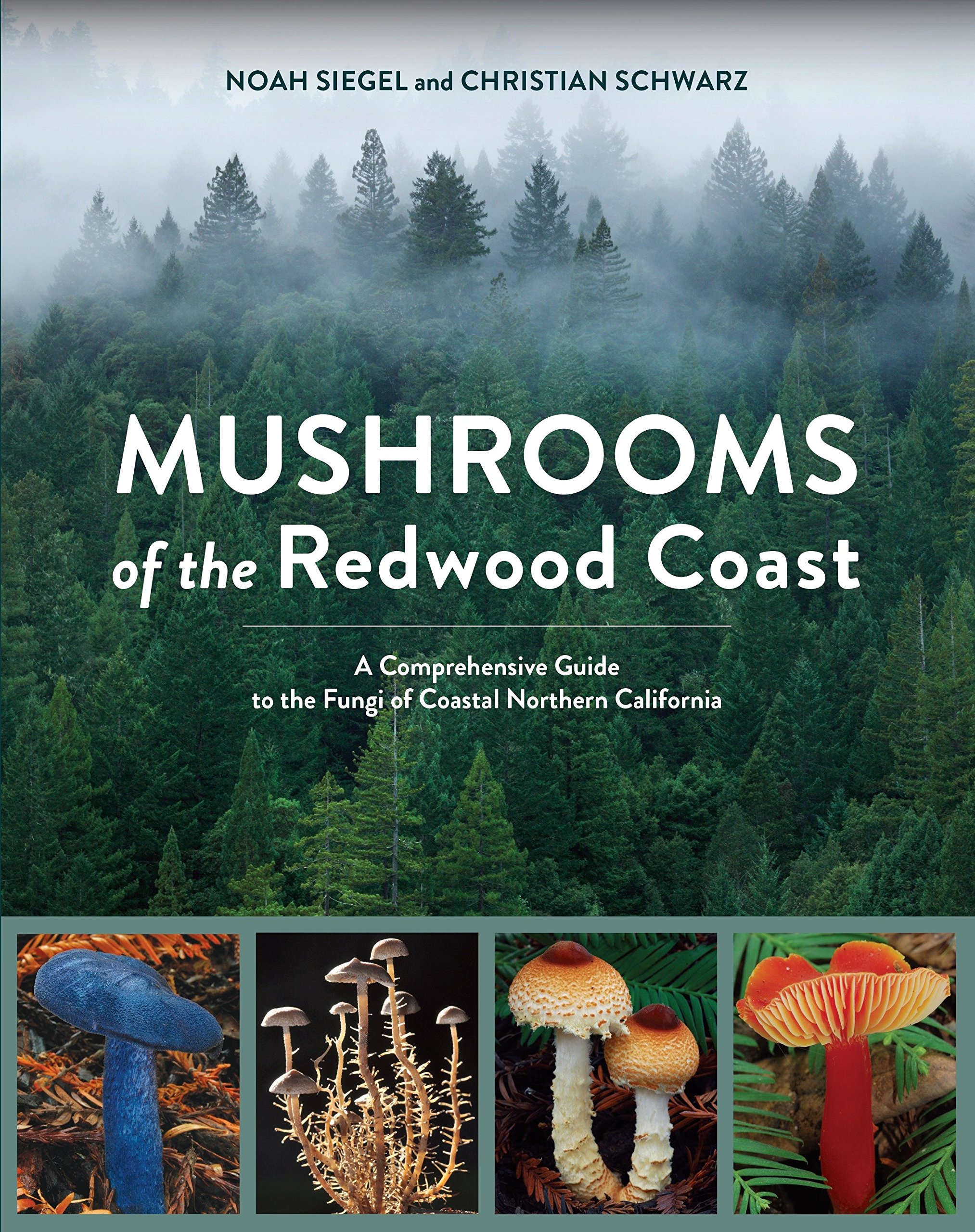

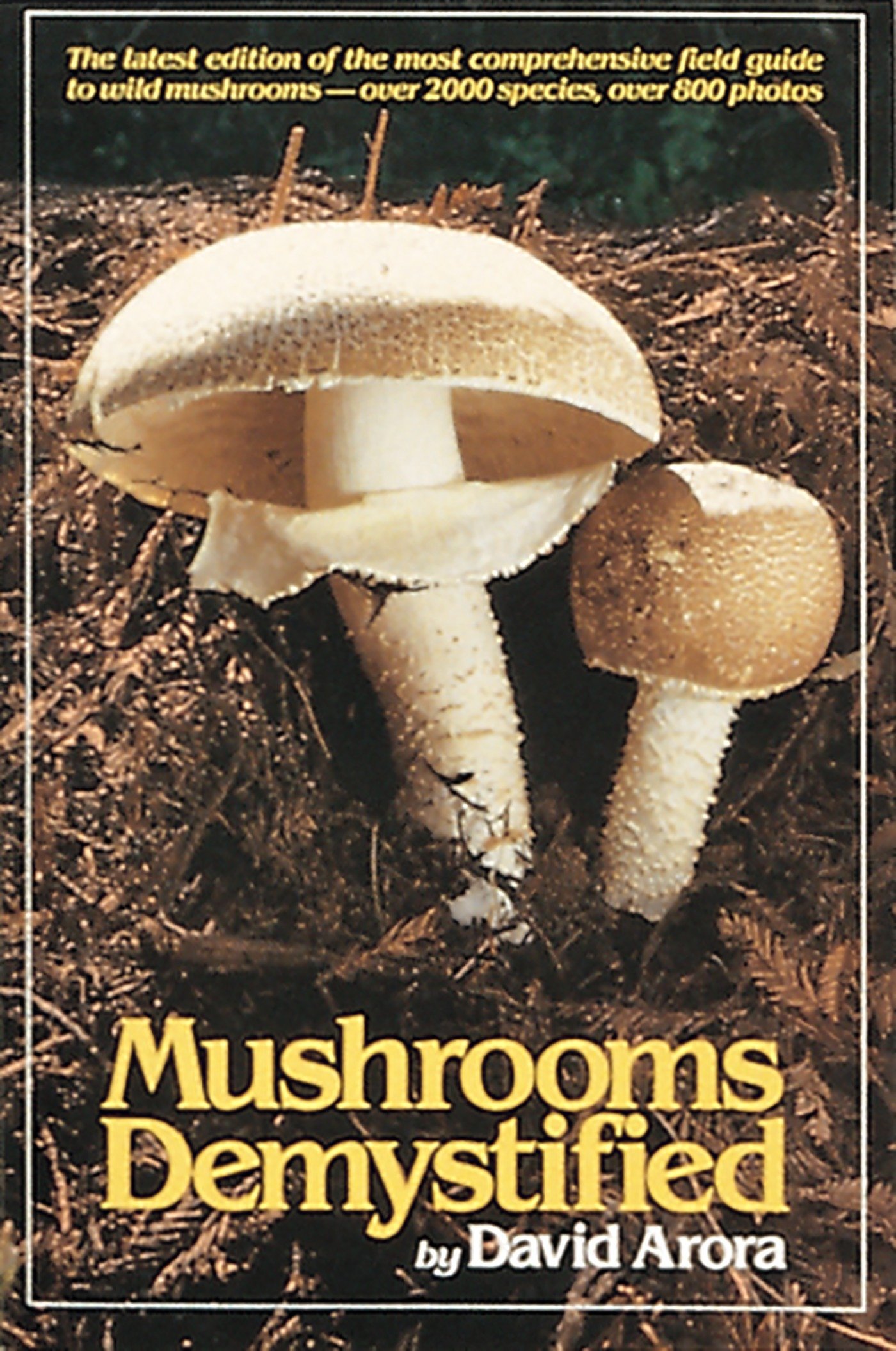

Our Recommended Field Guides for California

COVER | TITLE | Header | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

OUR #1 RATED | ||||

Edible Wild Mushrooms in California

Since we can’t tell you all about all the edible species in the whole state, we’ve decided to focus on a few regionally-distinctive species. It’s not that all these grow only in California, it’s that they are rare in most other parts of the United States.

Black Trumpet (Craterellus cornucopioides)

This Trumpet Mushroom[i] looks a bit like a thin-fleshed, almost papery, dark gray to black Chanterelle. The outer, spore-producing surface is pale gray, and the whole mushroom gets paler as it dries. It fruits in groups and prefers to grow near madrone trees or certain oaks. Reportedly, it is delicious. There are only two problems. First, it’s so small that eating a meal means picking a lot. Second, they’re hard to spot because they’re black. They blend into the shadows.

Western Cauliflower Mushroom (Sparassis radicata)

This odd mushroom[ii] takes the form of a dense ball of flattened, branching stalks with a long, root-like structure on the bottom. It does look vaguely like a head of cauliflower, or possibly like a bouquet of white or whitish wide noodles. Up until relatively recently, this species was sometimes confused with two other, similar species, one in eastern North America, one in Europe. But it is a distinct species. It is a choice edible, but can be hard to clean because of all the nooks and crannies between branches.

Blushing Morel (Morchella rufobrunnea)

This species[iii] is distinctive among morels in several different ways. On a practical level, it is one of the few that does not need to form a mycorrhizal partnership with a plant, meaning it can be, and is, cultivated. But just as intriguing is the fact that genetic studies have shown this to be the original morel species, the one all others descend from. These days, it can often be found growing in wood mulch, in planters, and on the sides of the road, mostly in California, Oregon, and Mexico. It’s recognizable because it bruises red or reddish.

Pacific Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus)

The golden chanterelle is a famous and sought-after edible. Some of the ones growing in the Pacific Northwest look a little odd, though. Genetic studies have shown that they are a distinct species, the pacific golden[iv]. It tastes about the same, but unfortunately for people who enjoy identifying mushrooms, there is a great deal of overlap in appearance between the two species—it’s not always possible to tell them apart.

Manzanita Bolete (Leccinum manzanitae)

Manzanita is a shrub of dry places with nutrient-poor soil. It’s distinctive of a certain kind of place where the Manzanita Bolete[v] likes to grow, though it also likes to share the habitat of madrone, an evergreen tree in the Arbutus genus. In any case, this large, reddish-brown mushroom is edible, though drying improves the flavor.

Salt-Loving Mushroom (Agaricus bernardii)

The salt-loving mushroom[vi] is wide-spread along seashores in both North America and Europe. When it grows inland, it’s usually (not always) near roads that are salted in the winter. It does not need salty soil, but seems to prefer it. It even smells briny. It’s a large gilled mushroom, white and smooth when young, becoming cracked or almost scaly and sometimes brownish with age. The shape of the ring on the stem is distinctive. That the flesh bruises red is even more distinctive.

Psychedelic Magic Mushrooms in California

As of this writing, psilocybin and any mushrooms that contain it, are still illegal to possess or use according to both Federal and California law. However, legislation has been introduced to decriminalize this and several other psychoactive substances, at least under certain situations[vii]. That will not change Federal law, though. It’s important to not use anything in this article in a way that sends anybody to prison.

And although most “magic” mushrooms are relatively safe to use from a medical perspective, they do have a toxic look alike. People have died by taking what they thought was a magic mushroom but wasn’t.

The following list is not necessarily exhaustive[viii].

Gymnopilus sp.

There are a lot of Gymnopilus mushrooms, but only a few are “active.” Mostly these are small and yellow-brown. Users often report that their high is qualitatively different from that given by the Psilocybes, suggesting that another active substance besides psilocybin may be in play. But few people use the gyms, so it is hard to say. California has four active gyms. Of these, G. luteofolius[ix] and possibly G. thiersii grow statewide, while G. aeruginosus[x] and G. dilepis are found only north of San Francisco.

Pluteus sp.

This is the same genus[xi] as such popular table fare as the deer mushroom, but a few of its members are “active.” In California, P. americanus[xii], which grows only in the north, is pinkish gray-brown but sometimes (not always) stains blue. P. brunneidiscus likewise does not grow in Southern California, but its key identification characteristics are not well described. These mushrooms are not well-known among psychonauts.

Panaeolus sp.

This group of mushrooms[xiii] are known as mottlegills for the dark splotches on their gills where patches of spores develop early—though psychonauts usually just call them pans. Some authorities separate out the few active species as the genus, Copelandia. Two active species, P. cinctulus[xiv] and P. olivaceus, grow throughout the state, but P. bisporus only grows to the south.

Psilocybe sp.

This is the best-known of the psilocybin-containing genera, thanks to the widely-cultivated Psilocybe cubensis, which is not a California native—but six others are. P. ovoideocystidiata[xv], known as the larger blue-foot, grows throughout the state and widely elsewhere as well. The others, P. allenii, P. cyanescens, P. pelliculosa, P. semilanceata, and P. stuntzii only grow to the north. Psilocybin Mushrooms are the most popular magic mushrooms for microdosing.

Poisonous Mushrooms in California

The following is not an exhaustive list, only some of the most dangerous and frequently-encountered species. It’s important to remember that there is no way to know whether a mushroom is poisonous without actually figuring out what kind of mushroom it is and looking it up. There are no simple things to look for, no rules of thumb that work in all cases, no short-cuts. There are people who honestly believe there are such short-cuts, and some write articles about mushrooms online, but foragers who attempt to follow simple rules in order to eat mushrooms they don’t really know sometimes end up in the hospital. Not all of them ever go home.

Amanitin-Containing Mushrooms

At least four of California’s poisonous mushrooms contain lethal doses of amanitins, poisons that not only have no known cure, but also kill very slowly. Symptoms don’t appear for anywhere from six to 24 hours after ingestion, but which time the toxin may be completely absorbed and the victim has likely decided that the mushroom meal was too long ago to be worth telling the doctor about. These first symptoms include intense gastrointestinal upset, but they tend to resolve after a day or two, possibly fooling everyone into believing the patient has recovered. What’s actually happening is that the toxin is destroying the patient’s liver and, later, kidneys.

People who think they may have eaten a mushroom containing this toxin should not give up, though. There is no cure, but treatment exists and occasionally works. The trick is to treat the symptoms and protect the liver and kidneys as well as possible and hopefully keep the patient alive long enough to flush the poison. Liver and kidney transplants save some people, too.

Not surprisingly, no one who wants to live eats these things on purpose, but all of these species have close look-alikes, plus more distant look-alikes that sometimes cause trouble when people don’t pay close attention to what they’re harvesting.

In California, at least three genera have at least some amanitin-containing members.

The Amanitas include several edible species, but most experts recommend never eating any of them for fear of misidentification. In the United States, the main reason is the Destroying Angel, a group of handsome, all-white, almost identical species that look almost exactly like certain puffballs in their early “egg” stage. They have also been mistaken for almost all the white or whitish edible gilled mushrooms at one time or another, even by experienced foragers, in a moment of inattention. Amanita ocreata is California’s species. California also has a serious problem with Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), a greenish-capped species not native to North America but introduced on the roots of imported trees. It still mostly grows in urban and suburban areas, where it is eaten by curious children and pets and by foragers not paying attention. Death cap closely resembles an edible Asian species, leading some recent immigrants to assume it is a taste of home.

Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata)

Galerina marginata[xvi]contains the same toxin but is not an Amanita. Instead, it is a “little brown mushroom,” or LBM, a large group that includes several popular edibles and most of the magic mushrooms. Worse, deadly galerina sometimes grows next to or among its look-alikes. It is possible to correctly and meticulously identify 99 mushrooms out of a clump of 100 as something safe and edible, shrug and harvest the last mushroom without checking, and then die because that last one was a deadly galerina. Check every mushroom.

Fatal Dapperling (Lepiota subincarnata)

Lepiota subincarnata[xvii]is one of a group of small parasol species, several of which are dangerously toxic. This one contains a lethal dose of amanitin[xviii]. While not all dapperlings are poisonous, it’s a good idea not to eat any of them, and even to avoid small specimens of some of the popular edible parasols, since they all look very similar. This one has a pinkish-brown cap and is white or whitish otherwise, with a sweet odor.

Western Jack O’Lantern (Omphalotus olivascens)

Jack o’lanterns[xix] are famous for two things: faintly glowing in the dark; and vaguely resembling the delicious golden chanterelle. A vague resemblance is enough to confuse some foragers. Eating this species is unlikely to kill anyone, but it will make eaters very, very sick. There are multiple species of jack o’lanterns, but this one is California’s.

Green-Spored Parasol or False Parasol (Chlorophyllum molybdites)

This mushroom[xx] is one of the shaggy parasols, a group whose members occupy a confusing continuum between dangerous and safe—they are sometimes poisonous, sometimes not. The so-called false parasol is the most frequently poisonous of the group. It is unlikely to kill, but should not be eaten.

My name is Austin Collins.

I've dedicated my life to Mushrooms.

I believe Mushrooms are the best kept secret when it comes to health and well being.

For that reason, I would like to share a company with you that in my opinion makes the best mushroom products on the market.

The company is called Noomadic Herbals, my favorite supplement they make is called "Mushroom Total".

I take their products every day and they have helped me think better and have more energy. Give them a try.

-Austin

References:

[i] Wood, M., Stevens, F. (n.d.). California Fungi—Craterellus calicornucopiodes. The Fungi of California

[ii] Wood, M., Stevens, F. (n.d.). California Fungi—Sparassis radicata.

[iii] Kuo, M. (2012). Morchella rubobrunnea. MushroomExpert

[iv] Kuo, M. (2019). Cantharellus fomosus. MushroomExpert

[v] Wood, M., Stevens, F. (n.d.). California Fungi—Leccinum manzanitae.

[vi] Kuo, M. (2017). Agaricus bernardi. MushroomExpert

[vii] Spiegelman, I. (2021). California Is One Step Closer to Decriminalizing Mushrooms, LSD, and Ecstasy. Los Angeles Magazine,

[viii] (n.d.). Which Psilocybin Mushrooms Grow Wild in My Area? Shroomery

[ix] (n.d.). Gymnopilus luteofolius. Philosophy

[x] (n.d.). Gymnopilus aeruginosus. Philosophy

[xi] Kuo, M. (2015). The Genus Pluteus. MushroomExpert

[xii] Kuo, M. (2016). Pluteus americanus. MushroomExpert

[xiii] (n.d.). Panaeolus. Wikipedia

[xiv] (n.d.). Panaeolus cunctulus. Philosophy

[xv] Roderick (2019). Psilocybe ovoideocystidiata. Psillow

[xvi] Wood, M., Stevens, F. (n.d.). California Fungi—Galerina marginata. The Fungi of California

[xvii] (n.d.). Lepiota subincarnata J.E. Lange—Fatal Dapperling. First Nature

[xviii] Wood, M., Stevens, F. (n.d.). California Fungi—Lepiota subincarnata. The Fungi of California

[xix] Wood, M., Stevens, F. (n.d.). California Fungi—Omphalotus olivascens. The Fungi of California

[xx] Wood, M., Stevens, F. (n.d.). California Fungi—Chlorophyllum molybdites. The Fungi of California