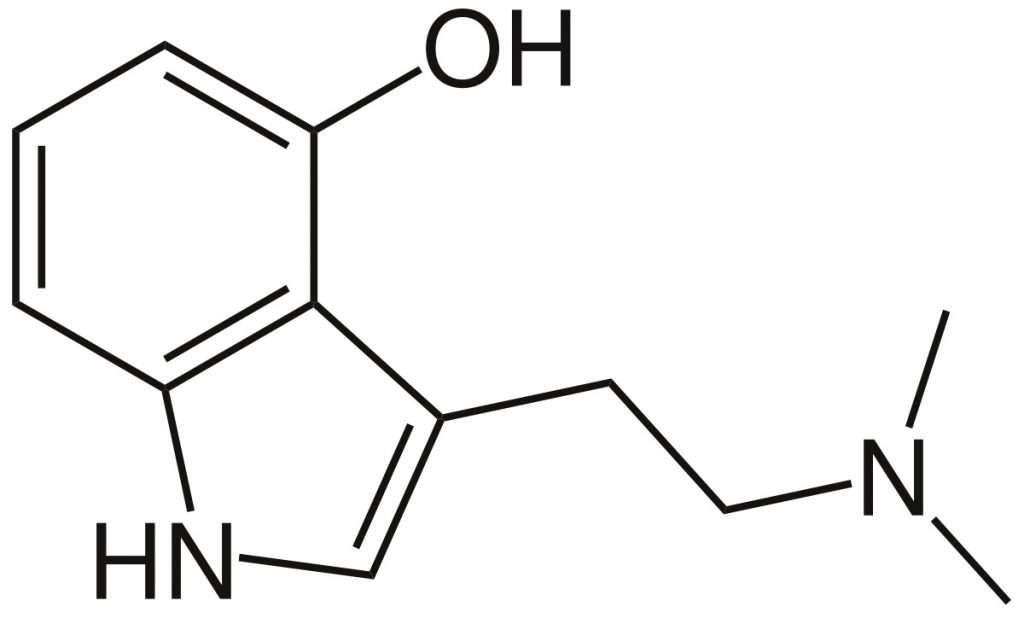

Psilocin (which is alternatively referred to as 4-HO-DMT, 4-hydroxy DMT, Psilocine, Psilocyn, or Psilotsin) is a substituted tryptamine alkaloid and a serotonergic psychedelic substance. It is present in most psychedelic mushrooms together with its phosphorylated complement, Psilocybin. It can thus be understood as a hallucinogenic alkaloid, and functions concomitantly as a fungal metabolite, a human xenobiotic metabolite, and a drug metabolite. Anecdotal reports describe synthetic, isolated Psilocin as more “lucid” and aggressive version than Psilocybin mushrooms when consumed alone.

Psilocin was first isolated by Swiss chemist Albert Hofman in 1958. Its psychoactive function is understood to stem from its similar chemical makeup to the neurotransmitter serotonin, which enables the Psilocin to interact with a wide range of serotonergic receptor sites in the brain. Thus, there has been some speculation and associated research that isolated or synthetic Psilocin may act similarly to Psilocybin mushrooms in terms of how it may treat issues with the Central Nervous System (CNS) and associated mental health issues such as clinical depression and chronic anxiety. This would be highly probable given that Psilocybin is a “prodrug,” of Psilocin, meaning it allows for the metabolism and conversion of Psilocybin into Psilocin in the digestive system after the consumption of magic mushrooms and can be understood as primarily responsible for Psilocybin mushrooms’ hallucinogenic and psychedelic effects.

Psilocin is not considered to be an addictive substance. However, it is not currently accepted for medical purposes in North America, and physicians caution that it has a high potential for abuse. As is the case with Psilocybin mushrooms, adverse psychological reactions to Psilocin may include severe anxiety, paranoia, and psychosis, particularly among those predisposed to preexisting mental illness.

Benefits & Uses

Serotonin

In a study published by the Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, researchers evaluated the effects of systematically administered Psilocin on extracellular dopamine and 5-HT concentrations in the ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, and media prefrontal cortex of the dopaminergic pathway in rats. Results indicated that administration of Psilocin increased dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens, and while it did not affect the extracellular 5-HT levels in the medial prefrontal cortex, serotonin was decreased in this region. These results indicate that Psilocin significantly affects the dopaminergic system in the nucelus accumbens and the serotonergic system in the medial prefrontal cortex.

Dopamine

As an active metabolite of Psilocybin, Psilocin is currently being investigated as a therapeutic agent for its effects on the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems in mammal brains. In a study published by the Journal of Psychopharmacology, researchers used a combination of genetic and pharmacological approaches to identify the serotonin (5-HT) receptor subtypes responsible for instigating the effects of Psilocin on the head twitch response and the behavioral pattern monitor in laboratory mice. Findings confirmed that Psilocin acts as an agonist at several serotonergic receptors in mice, suggesting that it could be utilized as an alternative solution to Psilocybin for development as a potential therapeutic agent in disorders of the brain that relate to the regulation of dopamine and serotonin levels, like clinical depression and generalized anxiety disorder.

Depression

Since Psilocin is an agonist at several serotonin receptors (including 1A, 2A, and 2C receptors), which are instrumental in the behavior of clinical depression, the alkaloid is being evaluated in the management of treatment-resistant depression, as is its counterpart, Psilocybin.

Several clinical trials have found that Psilocybin can rapidly improve depressive symptoms in certain sufferers, especially those that have treatment-resistant depression. The most rigorous study in this regard, which was headed by Stanford and enrolled 233 patients across Europe and North America, yielded that depressive symptoms such as suicidal ideation decreased significantly and over the long-term in Psilocybin-treated, depressed patients who were essentially non-responding to other forms of treatment like common antidepressants (SSRIS and SNRIS).

However, to date there have been no clinical studies specifically evaluating Psilocin as an isolated compound in the treatment of severe depression. That being said, given that Psilocin is the most potent psychoactive metabolite within Psilocybin mushrooms, and given that Psilocin is a serotonergic agonist, it is likely that the substance plays a role itself in the management of neurotransmitter activities that influence depression.

Anxiety, Panic, and Related Central Nervous System Disorders

Multiple lines of research have demonstrated that serotonin and related biochemical pathways are key elements in the manifestation of severe CNS disorders and related physiological and mental illnesses. As was previously mentioned, Psilocin is a highly effective serotonergic agonist, meaning it has the potential to impact depressive disorders, anxiety and panic disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, ADHD, OCD, and so on. Given their serotonergic receptor activities, psychedelic substances such as Psilocybin mushrooms are non-addictive and have long and persisting effects that are hypothesized to be beneficial for individuals with CNS disorders and mental illnesses.

A study published by Biochemistry Perspective explored Psilocin derivatives as serotonergic psychedelic agents for the treatment of CNS disorders and validated many of these hypotheses by evaluating the chemical structures of Mescaline, LSD, Psilocybin, and Psilocin alone. However, the researchers emphasized that there have been no placebo-controlled clinical trials related to CNS disorders in individuals or animals in relationship to isolated Psilocin alone. Thus, further research is needed in this regard.

Effects

Effects on the Brain

There are several effects associated with the use of Psilocin, which are both physical and cognitive. The cognitive effects of Psilocin are described by many as extremely relaxing and profound when compared to other commonly used psychedelics such as LSD, which tend to be more energizing and stimulating. Psilocin in isolation is also typically regarded as creating a more “lucid” effect than Psilocybin mushrooms but is not as “clarifying” as DMT.

- Cognitive enhancement and suppression cycles: Users often report waves of very profound thinking, which seem to undulate with periods of general thought suppression and mental intoxication in a cyclical manner.

- Emotionality enhancement: This effect can be described as being more consistent and profound when compared to other traditionally used psychedelics, such as mescaline or LSD. This can lead to strong feelings of compassion, empathy, and emotional sociability.

- Language suppression: Some users report a general unwillingness or even an inability to speak while using Psilocin.

- Creativity enhancement: Psilocin and Psilocybin are both associated with “out-of-the-box” ways of thinking, which tends to lead to a general enhancement of creativity.

- Cognitive euphoria: The pharmacological action of Psilocin has the potential to instigate a euphoric mood. However, under the wrong circumstances, it is important to bear in mind that Psilocin can have the opposite effect, creating anxiety and even mania.

- Color and visual acuity enhancement: Users of Psilocin often report a heightening of clarity of vision. Colors, shapes, and patterns typically appear more vivid and acute.

- Synesthesia: Synesthesia refers to an overlap of senses; for example, individuals experiencing this phenomenon might “taste” music or “see” sounds as colors.

- Distortions and hallucinations: Psilocin and Psilocybin are both associated with visual and auditory hallucinations and distortions in perception, which can be pleasant but also potentially distressing, which is why it is important to have a “trip sitter” when ingesting Psilocybin mushrooms, synthetic Psilocybin, or isolated Psilocin.

Negative cognitive effects can include memory loss, confusion, delusion, profound anxiety, and/or feelings of impending doom.

Effects on the Body

Physical/physiological effects of Psilocin can include:

- Sedation and perception of bodily heaviness: This effect corresponds to a general sense of sedation and relaxation that typically manifests with Psilocin use. This particular physical effect, which can also manifest in a feeling of heaviness and difficulty moving one’s limbs, seems to be primarily associated with the first half of the trip.

- Spontaneous, euphoric physical sensations: The “body high” of Psilocin has been described as a gentle and all-encompassing “glow.” This experience can be very euphoric and tranquil for individuals using the substance. These feelings tend to come and go in waves without any particular instigation.

- Tactile enhancement: This effect is less prominent than it is with LSD, for example, but is still prevalent with Psilocin use. Anecdotally, it can be understood as a “tingling” or ticklish feeling.

Negative physical/physiological effects might include “brain zaps,” or a feeling of being shocked or briefly electrified in the brain, muscle contractions, nausea, increased salivation, constant urination, sweating, chills, headache, or even, rarely, seizure (seizures more frequently occur when users are dehydrated, undernourished, or fatigued).

Dosage

How to calculate your dose

There is very limited research and even more limited anecdotal information available regarding the consumption and use of synthetic or isolated Psilocin. Accessing this substance on its own is quite a rare feat, so it is difficult to say what dosage is appropriate for the user per se. However, there is much information available regarding the consumption of magic mushrooms, which allow the consumer to access Psilocin as the active metabolite of Psilocybin, the naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in more than 200 species of hallucinogenic fungi. Therefore, it may be useful to revisit the appropriate dose of magic mushrooms here, as dosing is, of course, critically important when utilizing these substances.

In general, a low dose (1 gram) of Psilocybin mushroom is likely to contain about 10 mg of Psilocybin, whereas a medium dose (1.75 grams, roughly) will correlate to about 17.5 mg of Psilocybin. A high dose (3.0 grams and above) will have roughly 35 mg of Psilocybin. Any of these doses will instigate a psychedelic experience, the intensity of which will vary depending on dosage.

Also worth noting is that different types of magic mushrooms will contain different percentages of Psilocybin per weight of the mushroom. Psilocybin azurescens, for example, has 1.78% Psilocybin, Psilocybin bohemica has 1.34%, Psilocybe cyanescens has 0.85%, and the most common type, Psilocybin cubensis, has 0.61%. The more Psilocybin a mushroom has, the more potential it has to convert this substance to Psilocin, the primary active substance that causes hallucinatory and psychedelic effects.

Dosage Levels

In recent years, microdosing Psilocybin mushrooms has become quite popular. Microdosing refers to the consumption of sub-hallucinogenic quantities of magic mushrooms. Individuals who microdose often do so to manage stress, anxiety, or depression, clarify cognition, stimulate creativity, and regulate the mood.

To revisit, Psilocybin is actually not the primary bioactive component of magic mushrooms that causes its hallucinogenic effects. Psilocybin is known as a “prodrug,” a biological compound that can be metabolized to produce an active metabolite. When you consume magic mushrooms, Psilocybin is metabolized into Psilocin. So, if you microdose, you are bypassing that process and avoiding the hallucinogenic properties afforded by Psilocin metabolism.

If you wish to microdose, you’ll be taking about one-tenth of a hallucinogenic dose of magic mushrooms, which is often around .3 grams but can be as low as .35 grams. Microdosing might be a good option for individuals who are interested in trying Psilocybin mushrooms but don’t feel quite ready for the heady, hallucinogenic effects afforded to the fungi by its Psilocin metabolite.

Some people even opt for a heroic dose which is only suggested for experienced users as it causes you to lose touch with reality.

Side Effects, Safety & Toxicity

Like Psilocybin, Psilocin is non-addictive and has extremely low toxicity relative to dose. Similar to other psychedelic drugs, there are relatively few physical side effects associated with acute Psilocin exposure.

In rats, the average lethal dose of Psilocybin when administered orally is 280 mg/kg. Psilocybin comprises about 1% of the weight of Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms, for example, and so nearly 1.7 kg (3.7 lb) of dried mushrooms or 17 kg (37 lb) of fresh mushrooms would be required for a 60 kg (13 kg) person to reach the lethal dose value.

Despite its lack of physical toxicity, however, it is still considered a drug with a high potential of abuse in certain individuals, particularly those with preexisting mental health conditions. It is strongly recommended to utilize harm reduction practices when taking hallucinogens of any kind.

These can include:

- Avoiding unfamiliar, loud, cluttered, and/or public environments.

- Finding out the best way to take Shrooms for you.

- Avoid doing dangerous activities while tripping. (See: Best Things to do on Shrooms)

- Avoiding people who are not directly participating in the experience.

- Making use of a “trip sitter,” or someone who will responsibly look after you in case of a negative trip.

- Avoiding exposure to unpleasant or disturbing stimuli, like horror films or ominous music.

- Avoiding use of hallucinogens when in an acutely stressful or negative period of life.

- Avoiding use of hallucinogens when exhausted, ill, or injured.

- Never “guestimating” your dosage – calculate it carefully (You can use a Magic Mushroom Dosage calculator for that)

Psilocin vs Psilocybin

To review, Psilocybin is actually a “prodrug,” not the primary active compound in magic mushrooms. This means that Psilocybin facilitates its own metabolism into Psilocin, the active metabolite that likely produces psychedelic and hallucinogenic effects produced by the consumption of magic mushrooms. More specifically, when magic mushrooms are consumed by humans, the liver converts Psilocybin into the psychoactive molecule Psilocin. While Psilocybin receives most of the credit for its mood and perception-altering properties, Psilocin is most likely the molecule that creates most of the psychoactive effects. We say, “most likely,” because the ways in which Psilocybin and Psilocin behave in the brain are still being researched; after all, it is exceedingly difficult to track neurotransmitter activity precisely in the human brain.

Chemical Structure

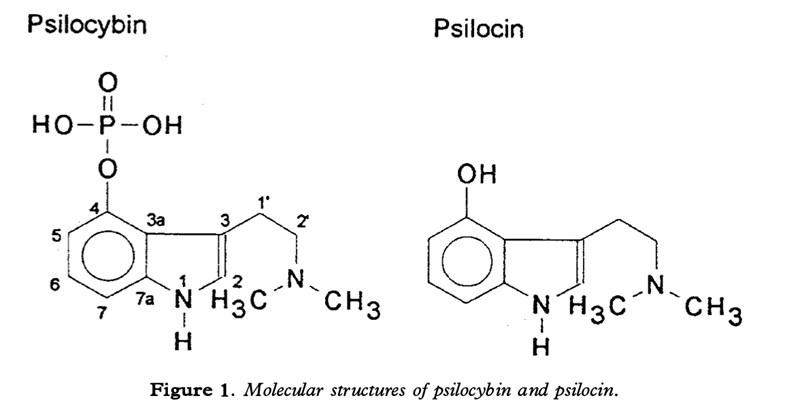

As one can observe in the two molecular structure images pictured above, Psilocybin and Psilocin are markedly similar. The only difference lies in the position of the hydroxylgroup. Thus, the primary behavioral difference between these two molecules comes down to stability. For example, Psilocin is a relatively unstable compound in solution. Under alkaline conditions, it forms bluish and black degradation products.

Mechanism of Action

Because the main method of taking mushrooms is via oral ingestion, any Psilocybin (O-Phosphoryl-4-hydroxy-N) molecule that is ingested is broken down into Psilocin (4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-tryptamine) in the digestive tract by the enzyme alkaline phosphate. Eventually, the body breaks Psilocybin and Psilocin down completely, using mono-amino oxidase enzymes, after which process these molecules are excreted from the body, mostly via urine.

Best Ways to Take Psilocin?

It is possible to access synthetic Psilocin, but it is very rare to acquire this substance unless one is working in a lab or otherwise directly researching its effects. If you’re interested, your best bet is to access Psilocin’s hallucinogenic effects by (wisely, legally, and conscientiously) ingesting Psilocybin mushrooms.

Legalization & Decriminalization

If Psilocybin mushrooms are illegal in any given country or region, this means that Psilocin is criminalized as well. In some countries, Psilocybin mushrooms are technically illegal, but decriminalized in certain areas, and in others, there are legal loopholes that sometimes allow for magic mushroom use. A few examples of such instances are detailed below.

Canada: Psilocybin and Psilocin are illegal to possess, obtain, or produce without a prescription or a license, given that they are classified Schedule III under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

United States: Psilocybin and Psilocin are illegal Schedule I drugs, so they are technically illegal, though some regions have decriminalized Psilocybin mushrooms, such as the cities of Denver, Colorado, Oakland, California, and Santa Cruz, California.

United Kingdom: According to the 2005 Drugs Act, Psilocybin and Psilocin are Class A substances, along with heroin, cocaine, ecstasy, and LSD.

Mexico: The possession, growth, sale, and consumption of mushrooms is illegal. However, rules tend to be relaxed regarding use of these substances in terms of spirituality and religious practices.

The Netherlands: The possession, growth, sale, and consumption of magic mushrooms is illegal, and thus are Psilocybin and Psilocin for recreational use. However, due to a legal loophole, Psilcobyin truffles can be legally possessed, grown, sold, and consumed.

Australia: Psilocin is considered a Schedule 9 prohibited substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard, meaning the manufacture, possession, sale, or use of Psilocin is prohibited except when necessary for scientific or biomedical research.

Interactions

Psilocin has hallucinogenic effects and is a serotonergic substance, meaning it increases serotonin in the brain. Numerous prescription medications also have this effect, and thus interactions with other serotonergic drugs may increase serotonin levels too much, leading to serious reactions that range from agitation, insomnia, confusion, and high blood pressure to high fever, seizures, tachycardia, and even death. Therefore, taking Psilocybin mushrooms – and especially synthetic or isolated Psilocin – with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, analgesics, and antibiotics is strongly contraindicated.

Stimulants also interact with Psilocin and Psilocybin. These include illegal, recreational stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine, as well as prescription stimulants such as dextroamphetamines and dextromethylphenidates that treat ADHD, narcolepsy, and depression, and even everyday stimulants like caffeine or nicotine. Interactions with these drugs can result in severe anxiety, increased body temperature, tremors, seizures, coma, or death in very rare cases.

Synthetic Psilocin

Psilocin in its synthetic form is only ever rarely utilized. Synthetic Psilocin can be obtained by dephosphorylation and natural Psilocybin under acidic or alkaline conditions (hydrolysis). Another synthetic method utilizes Speeter-Anthony tryptamine synthesis.

Psilocin is a relatively unstable active ingredient in Psilocybin mushrooms. Because of this, synthetic processes must “mimic” nature’s protection by attaching phosphates that protect oral and gut tissues from the corrosive effects of the mushrooms. Chemical reactions necessary to isolate Psilocin and convert it to Psilocybin require very particular temperatures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Does Psilocin show up on a drug test?

Standard panel drug tests do not typically look for magic mushrooms. However, there are specialized tests that will detect both Psilocybin and Psilocin in the urine. Hallucinogen tests may include markers for LD, mushrooms, mescaline, and peyote. There is also, of course, a risk of magic mushrooms becoming contaminated by other detectable drugs if one acquires the fungi from an untrustworthy or unsavory vendor.

It is also worth noting that the body breaks down Psilocin relatively quickly. Most people can expect the compound to be out of one’s system after a day. As these compounds are excreted via urine, one may be able to flush Psilocin from the system sooner by drinking a good amount of water (this is an anecdotal claim though; there is no clinical evidence that this is necessarily true).

What is the half-life of Psilocin?

Psilocin is renally excreted, and about 2/3 of excretion occurs in the first 2 hours after consumption. The half-life is about 50 minutes. After 24 hours, Psilocin is undetectable in urine.

References:

National Center for Biotechnology Information (2022) PubChem Compound Summary for CID 4980, Psilocin.

Psilocin (n.d.) In Psychonautwiki.

Albert Hoffman (n.d.) Albert Hoffman Foundation.

Madsen M.K., Fisher P.M., Burmester D., Dyssegaard A., Stenbæk D.S., Kristiansen S., et al. (2019) Psychedelic effects of psilocybin correlate with serotonin 2A receptor occupancy and plasma psilocin levels. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44: 1328-1334.

Kargbo R.B. (2021) Psilocin Derivatives as Serotonergic Psychedelic Agents for the Treatment of CNS Disorders. ACS Publications, 12(10): 1519-1520.

Psilocybin and psilocin (Magic mushrooms) (n.d.) Government of Canada.

Sakashita Y., Abe K., Katagiri N., Kambe T., Saitoh T., Utsunomiya I., et al. (2015) Effect of psilocin on extracellular dopamine and serotonin levels in the mesoaccumbens and mesocortical pathway in awake rats. 38(1): 134-138.

Halberstadt A. L., Koedood L., Powell S. B. & Geyer, M. A. (2011). Differential contributions of serotonin receptors to the behavioral effects of indoleamine hallucinogens in mice. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(11): 1548–1561.

Madsen M.K. & Knudsen G.M. (2021) Plasma psilocin critically determines behavioral and neurobiological effects of psilocybin. Neuropsychopharmacology, 46: 257-258.

Goldhill O. (2021, November 9) Largest psilocybin trial finds the psychedelic effective in treating serious depression. Stat News.

Mackenzie R. (2021) An Introduction to Five Psychedelics: Psilocybin, DMT, LSD, MDMA, and Ketamine. Neuroscience News & Research.

Sellers A. (2021, October 3) What are magic mushrooms and psilocybin? Medical News Today.

Ghose T. (2014, October 29) Magic Mushrooms Create a Hyperconnected Brain. Live Science.

Dudysová D., Janku K., Šmotek M., Saifutdinova E., Koprivová J., Bušková J., et al. (2020) The Effects of Daytime Psilocybin Administratino on Sleep: Implications for Antidepressant Action. Frontiers in Pharmacology.

Hartney E. (2022) What to Know About Magic Mushrooms

Jikomes N. (n.d.) How to dose psychedelic mushrooms.

Roderick (2019) How Much Psilocybin is in a Gram of Mushrooms

Anderson T., Petranker R., Christopher A., Rosenbaum D., Weissman C., Dinh-Williams L.A., et al. (2019) Psychedelic microdosing benefits and challenges: an empirical codebook. Harm Reduction Journal.

Zhuk O., Jasicka-Misiak I., Poliwoda A., Kazakova A., Godovan V. V., Halama M. & Wieczorek, P. P. (2015) Research on acute toxicity and the behavioral effects of methanolic extract from psilocybin mushrooms and psilocin in mice. Toxins, 7(4): 1018–1029.

Psilocybin Mushrooms (n.d.) Harm Reduction.

Passie T., Seifert J., Schneider U. & Emrich H.M. (2002) The pharmacology of psilocybin. Addiction Biology, 7: 357-364.

Hallucinogenic mushrooms profile (n.d.) European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.